|

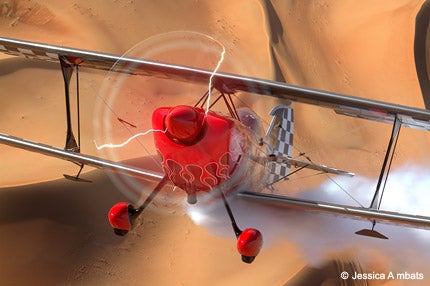

I’m an air show pilot who’s known for making my performances look dangerous. I fly through fire that shoots from the back of a jet truck, I pass under jumping motorcycles, I maneuver close to exploding bags of gasoline. I perform some of the lowest-level aerobatics that you’ll see anywhere. So it may come as a surprise for some to hear me talking about safety. But just like with every other aspect of aviation, safety is always a primary concern—whether I’m making a knife-edge pass in my highly modified Pitts S-2S, Prometheus, or transporting cargo in a Boeing 727 for my “day job” at FedEx.

We all strive for perfection in aviation—whether shooting the perfect ILS approach or executing a seamless aerobatic loop. For me, the key is being comfortable. The first time I shot an approach under the hood was much like the time I flew my first loop. It’s new, exciting and evokes the “fight or flight” response with which we’re all born. That usually means tunnel vision and time compression: a feeling of time passing by more quickly. With practice, a complete vision returns, time seems to slow down, and learning the nuances of the maneuver can be realized.

The maneuver I’m probably known best for is a high-alpha, knife-edge takeoff, where I keep my Pitts’ wingtip a few feet from the ground while flying down the runway at minimal speed. At first glance, one would think that an engine failure would result in the airplane falling out of the sky. It actually takes about 15 mph more airspeed to fly the fuselage than it does the wings. If an engine failure does occur, simply rolling the wings slowly toward level has the same effect as flaring for landing.

Air show flying helps me become more comfortable with other types of flying. Unlike most airline pilots I’ve flown with, having an engine failure in a large multi-engine airplane isn’t the most dynamic thing I’ve experienced. When I’m flying my Pitts, I’m flying a single-engine airplane, with one alternator, basic instrumentation and the glide ratio of a frying pan at less-than-ideal altitudes. When I compare that to flying a large transport category airplane that has three engines and double or triple redundancy on just about everything else, it’s hard to be worried too much about something failing. Expanding my envelope of comfort through flying aerobatics helps me remain calm when dealing with what may otherwise be stressful situations in other types of aircraft.

Air shows are essential to the future of general aviation. More than 10 million spectators attend air shows each year, according to the International Council of Air Shows. As a teenager, I was inspired watching air show pilot Leo Loudenslager—it was the moment when I realized that “good enough” wasn’t going to be good enough. If I wanted to be in a position to inspire others in the way that I had been inspired, it meant I had to apply myself in school and make good decisions. It’s important that we expose aviation to as many young people as possible.

Usually, when we talk about air show safety, we’re talking about the safety of the spectator. But at a recent show outside of the U.S., it was the pilot’s safety that I found myself concerned about. The rules adopted for the show were from the UK, and included a stipulation that pilots can’t fly below 50 feet AGL. That posed two major problems for me. It’s a cardinal rule that you not change your practiced routine while at a show. Even the smallest changes can have a great and sometimes unexpected result. I fly below one-half of my airplane’s wingspan, which increases performance due to ground effect. That means more airspeed gains in a shorter distance. Losing the additional performance is cumulative, as each pass will have less and less energy. Timing, altitude cues and target airspeeds can all change. How much? I’m not sure, but I didn’t want to find out in front of my fans halfway around the world, so I chose not to fly my routine with the imposed changes.

|

Furthermore, if the rules are too strict, it can compromise a pilot’s ability to entertain the fans. In today’s hi-def, computer-animated, sensory-overload world, it’s becoming more difficult to keep the air show fan’s attention. Having rules that unnecessarily compromise entertainment value would lead to the demise of the air show industry, which could adversely affect general aviation as a whole.

The rules we fly by in the U.S. are spot-on. There are two primary rules from which the rest are based. For one, there are minimum set-back distances from the crowd for aircraft, which are based on the aircraft’s cruising speed or weight. Generally, this means that propeller-driven aircraft can fly closer to the crowd than jet-powered aircraft. This is why when you go to a show, you’ll see Extras and Pitts flying much closer than an F-16 demo, for example. Unlike a car-racing event, where there can be a physical barrier between fans and race cars, these set-back distances are used as the only barrier that pilots have. How well does this system work? Well, we haven’t had a spectator fatality at an air show since 1952, and the same can’t be said for the rest of the world.

The second primary rule deals with energy directed toward the crowd. This is to say that if an aircraft were to have a catastrophic disassembly, the debris from the airplane wouldn’t continue into the crowd, because the maneuver that had been flown wouldn’t have been “directing energy toward the crowd.” This is especially important when there are several aircraft flying in formation, since one aircraft clipping another has caused many of the accidents in other parts of the world. It’s this rule that would have saved so many lives if it had been adopted by other countries.

What do these rules have to do with pilot safety? Absolutely nothing. Training, practice and a peer-group evaluation program implemented by the FAA and run by the International Council of Air Shows (ICAS) help to ensure that the pilots given a Statement of Acrobatic Competency are just that—competent. There’s a multiple-tier progression that requires a pilot to fly higher for their first several air shows, and then get evaluated before being allowed to go down to the next lower altitude. This process allows the pilot to get used to the pressures of flying in front of people. It also gives the opportunity to their peers to voice possible concerns to the pilot and evaluators before the pilot is allowed to fly at lower altitudes. This is very important, since a lower altitude will require a much greater level of discipline due to the reduced cushion. Once a pilot has achieved a ground-level waiver, the system has ensured that the pilot has passed several evaluations and has had quite a bit of “in front of a crowd” flying. Annual evaluations are then all that’s required. From this point on, the pilot has earned a lot of respect and takes on a lot of responsibility.

It’s a tremendous amount of responsibility to keep a crowd safe. Each air show pilot is allowed to determine the level of risk they’re willing to mitigate in order to entertain the fans. Making sure we fly on the safe side of the safety-versus-entertainment equation is up to us as professionals. As long as the defined set-backs aren’t broken and no energy is directed toward the crowd, you can do whatever you want. And let me tell you, that’s a feeling of freedom that’s hard to describe.

Skip Stewart has over 8,000 hours of flying experience, and is an ATP and a CFI. He has earned gold medals in regional aerobatic competitions, served as a chief pilot for a Fortune 100 company, and has spent more than 11 years entertaining air show fans around the world. Visit www.skipstewartairshows.com.