|

Here’s an aviation fact that you can take to the bank knowing it’s almost always true: Neither the wind given to you by the tower, nor that shown on a mid-field wind sock, is likely to be what you actually experience when landing. There are lots of reasons for that, and understanding those reasons will cut down the number of surprises and the amount of drama in your crosswind landings.

1 A Steady Wind Isn’t Even Remotely Steady If wind had color, so we could actually see how it’s shaped, we’d see that like a river, it’s interrupted by swirls and eddies. It’s constantly changing, flowing smooth for a few seconds, then changing direction and strength, only to go smooth again. So when we’re in the approach and, even more important, when we’re in flare and floating down the runway, we’re experiencing an ever-changing combination of wind-induced bumps and wiggles. Every several hundred feet down the runway promises a new experience.

2 Wind Is Made Up Of Layers When thinking about fighting wind, we often think of nothing but crosswinds, which is a two-dimensional, left-right way of thinking. However, wind, like airplanes, is three-dimensional, and is usually composed of several layers. It’s quite common to turn final and find that our glideslope has changed. At first we looked high, then for no apparent reason, we’re low (the numbers are moving up the windshield), and a few more ponies are needed to make the runway. Or, just the reverse happens. This is because the wind at pattern altitude is much less affected by either the friction wind develops with the ground, or the topography and other ground-bound obstacles that the wind has to work around. Also, thermal effects are generally more intense closer to the surface. So, don’t be surprised to find that the wind on the ground is grossly different than what was experienced on downwind.

3 Topography Can Really Affect Wind On Short Final Not all runways are in the middle of a mile-square, billiard-like wheat field. In fact, in many parts of the country, runways are perched on, carved out of, clinging to or stuffed into real estate that’s everything but flat. And that being the case, the wind’s path can be pretty screwy because of what it’s curling over and around.

A curl is developed when the wind has to avoid an object and, in effect, wraps itself around the corner, e.g. a runway with a noticeable drop-off at the end. When the wind comes whistling down the runway and the pavement is suddenly no longer there, the wind curls downward. If we’re on short final, the curl will try to take us with it.

The reverse of the downward curl is when we’re coming over an obstacle at the threshold directly into the teeth of the wind that’s trying to climb over that obstacle. It will pick us up, then just as quickly, decide it no longer wants us, and where we were fighting an upper, we’re suddenly falling out of the air.

Another variation of curl occurs when we’re landing in a crosswind—a time when we really don’t need any more complications—on a runway with a ridge or tree line alongside it. This time, the curl is coming over the trees, and it may try to slam you into the ground. It may try to pick you up. It may just pound you senseless, then smooth out, as if saying, “Okay, I’ve screwed with you enough.”

4 Wind Socks At The Beginning Of The Runway Are Best We always try to land at the beginning of the runway (if we’re doing our jobs anyway). Unfortunately, most airports think we land in the middle of the runway because that’s where they put the wind sock. Socks can’t be that expensive! Every runway should have a sock at each end, so we actually know what the wind is doing where we’ll be touching down. The further down the runway a wind sock is located, the closer to fantasy it becomes.

Some specifics: You’re landing on a 5,000-foot runway and the only sock is mid-runway. That’s nearly a half-mile from where we’ll land. We can fit a lot of wind changes into a half-mile. Especially if the wind is crossed, and there’s topography or buildings out there adding their little bit of entertainment to the situation.

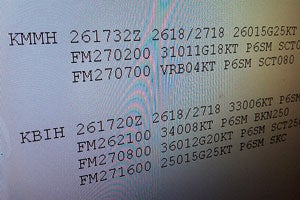

5 Control Towers Often Get Wind Information From Off-Airport Sources It’s common for the source of wind information broadcast on ATIS, especially at larger airports, to be off of the airport property. So, this time it’s an 8,000-foot runway, and the wind information is coming from a tower that’s a quarter-mile away: Now, we’re landing nearly two miles from the wind information source. Yet another reason why we search out secondary wind information sources, such as wind socks, flags, blowing dirt, trees, etc.

6 Beware The Down-To-The-Surface Wind One of the more unusual winds is the one that ignores boundary layer effects. As a normal rule, the wind right on the surface of the runway is zero, and it builds up to the reported velocity at about 15 feet. However, there are some “rogue” winds that hold much of their velocity right down to the pavement. This is just the reverse of what normally happens. In this case, the airplane is slowing down and losing energy, while the wind is doing neither. Because the wind hasn’t decreased, its effect on the airplane is actually stronger. These can be really, really nasty winds because they sneak up on you, and you don’t realize until the last second that it takes much more control movement than normal to beat them into submission.

The topography of a runway can change the path of the wind, sometimes quite dramatically. A wind curl is developed when the wind has to avoid an object and in doing so, it wraps itself around the corner. |

7 Violent Changes In Direction Can Steal Lift One of the most dangerous winds doesn’t even have to be a big one. It can be less than 15 knots and still cause plenty of heartburn. It will have two characteristics that fortunately aren’t combined that often, but the combination occurs often enough that it’s worth discussing.

The first characteristic is sharp-edged gusts that change direction in a heartbeat. Making it much worse, the sharp peaks of the harder-than-normal gusts are off the main wind heading. As the gust dies, the wind returns to the main heading. So, every time it punches you, it’s from a different direction at a higher velocity.

The second characteristic is that the basic direction of the wind is 90 degrees to the runway. When a 90-degree wind is combined with sharp gusts that snap back and forth during flair, the possibility of gusts instantaneously changing from in front of the wing tip to behind the wing tip becomes critical. When wind snaps from in front to behind the wingtip, the airplane doesn’t have time to react to the sudden change in airspeed because of inertia. For a moment, it loses so much lift that it becomes dynamic, as opposed to aerodynamic. At that point, it’s an ingot, not an airplane. This is when burying the throttle in the panel is called for. Not partial power. Full power, because nanoseconds count.

8 Wind And Turbulence Interact One of the more “fun” wind conditions (read that as teeth-shattering because of the violent ups and downs) is seen in the West more than any other place. This is when a hard-edged, gusty wind is combined with low-level turbulence caused by high ground temperatures and/or topographical effects. The resulting ride can be violent and unpredictable. In these conditions, our primary job is to determine exactly what attitude is required to counter the crosswind, and how to “firmly” maintain it without over doing the corrections. When fighting turbulence in gusty crosswinds, there’s a tendency to accidentally bring the ailerons back “past center.” By this, we mean that we’re supposed to be holding a wing down, but without realizing it, we overcontrol in turbulence and actually put aileron in the other direction. This momentarily picks up the down wing.

When fighting those kinds of conditions,we have to visualize the exact wing attitude we need for the crosswind correction, then be very firm with the controls, making smooth, but quick jabs to maintain that attitude and keep the nose right in front of us. We don’t want the wind to fly the airplane. That’s our job.

9 Ground-Level Venturi Effects “Whoa! What was that?” We’ve all felt it on either landing or takeoff. Everything will be going just great, when we’re hit with something from the side that feels as if we’ve gone through a jet-engine blast. Usually, it’s a narrow steam of wind caused by a crosswind flowing between two obstacles (buildings, trees, etc.). The venturi formed by those obstacles causes the wind to narrow and accelerate, creating the jet-blast effect. These are quite often formed only during specific wind conditions, e.g. for a given airport, it may be a wind from 030 that happens to line up with a venturi-like gap between a building and a billboard, or something similar.

10 The “Character” Of The Wind Is As Important As Direction Or Velocity It’s not unusual to find ourselves working our butts off in a little 12-knot wind when we know that we’ve handled 25-knot winds with far less work. All winds aren’t created equal, and it’s the character of the wind that makes up much of the difference. Is it quirky with some sort of weirdly changing direction, or it’s three knots, gusting to 12 knots and the changes are instantaneous, so you often get left hanging? The personality types of wind are almost limitless. The good news is that by studying the wind sock and the local environment, you can get a rough idea of the general character of the wind you’ll be fighting.

The winds you actually experience when landing may be different from those that were reported. Factors such as topography and venturi effects will all come into play. |

If the sock goes from practically limp to fairly straight, we know we’re going to have a bumpy, unpredictable ride. If its “stiffness” remains fairly constant, but it’s whipping back and forth, we’re going to be working hard to maintain an attitude. If it has very little wind in it, but it periodically circles the mast in a lazy fashion, there’s a chance we may be landing with a slight tailwind. If it’s at 90 degrees to the runway, with regular excursions to 120 degrees (30 degrees behind the wing) and is gusting 15 to 25 knots, it might be a good day to visit the airport restaurant and wait until Mother Nature makes up her mind.

Pay special attention to everything around the airport and the runway that can indicate wind. This includes flags, hanging decorations on businesses, tethered balloons, etc. If you see a flag that’s off-airport that indicates a wind that’s quite a bit different than the sock, you know something exciting is happening in between. If the grass next to the runway is laying flat, you know it’s one of those “nasties” that retains its velocity right down to the surface. Watch out!

Summary

A runway is nothing more than a long string of micro climates, little bubbles of wind, temperature, humidity, etc. that change as we travel down the runway from bubble to bubble. Knowing that arms us with one very important fact: Regardless of what the tower or wind sock tells us, we should be prepared to deal with whatever we’re seeing around the airplane at any given moment. The old adage, “Fly the airplane,” applies here. If something is making it do something you don’t want it to do, we don’t really care what’s causing it. We just do our pilot thing and put the airplane where we want it.

Incidentally, there’s no takeoff that absolutely has to be made. If the wind is too far out of your comfort zone, don’t fly. And we should never allow a fuel situation to develop that forces us into making a landing in a wind condition we think is over our heads. Always be prepared to go looking for an alternate airport with friendlier winds.