|

On a recent cross-country on a busy day in the skies above California, I got a firsthand look into the importance of a good headset, and how a headset that’s good in one airplane might be completely wrong in another. I was in the rear seat while the airplane’s owner was handling the radio. She was wearing a name-brand, top-of-the-line headset. Every time she would transmit to make initial contact, ATC would invariably ask her to repeat herself. “Ahh, is that one fife mike lima?” they would ask a third time, as if we had spoken gibberish, “And say again type air-

craft?” My friend would then patiently answer in her clearest voice, “No, it’s one niner mike kilo and it’s a Decathlon-type bravo lima eight.” Eventually, they would get it right, and it would start again at the next handoff.

This was an example of the wrong headset in the wrong airplane. The headset she wore sounded fantastic in most airplanes. It has ANR (active noise reduction) and an excellent microphone, albeit one that was designed for quieter cockpits. Decathlons (like Super Cubs and many other airplanes) are particularly noisy in the cabin. They have an abundance of two things: a loud, low-frequency hum and a great amount of high-frequency noise from air flowing over the boxy fuselage. The fuselage also acts like a guitar body, amplifying the noise. It’s a very unique cockpit environment. It’s not good or bad, it just is.

My friend’s expensive headset—with the unprotected microphone designed for average GA cockpits—was transmitting all the aircraft noise in the cabin. It wasn’t a problem with the headset; it was just the wrong environment for that particular one. I wore my less expensive, passive headset that I wear in open cockpits. I selected that particular headset and tweaked it until it gave the best results possible in that loud environment. It was a simple example of picking the right tool for the job. Mine is a headset tailored to a particular environment.

Defining The Mission

Pilots talk quite a bit about “the mission,” that is, the intended and normal use of the aircraft they’re flying. Whether buying an aircraft or buying a headset, defining that mission is critical. It means carefully examining the noise environment of your particular airplane. This simple step lets you avoid the problem and expense of buying the wrong headset. Remember that headsets are a combination of a receiver (the speakers in the ear cup) and the microphone (on the end of the boom), so it’s important to select a headset that’s a combination of the right components. In my case, my “mission” is short trips in the windy open cockpit of my old biplane.

My mission dictated a PNR (passive noise reduction) headset with a higher-output electret condenser microphone. It also needed to fit securely enough to stay on my head in the wind, and have high gain (the ability to turn the volume up) so I could hear ATC over the noise. I ended up with a Pilot USA PA-1181T with an upgraded microphone and mic-muff leather covers from Oregon Aero. I also opted for upgraded ear seals, and I changed the head pad to suit my needs.

The point to take away here is that an ANR headset wasn’t right for my mission. ANR attenuates (reduces) frequencies in the lower range. That’s because scientists have discovered that the “average” GA airplane produces a low-frequency hum in the 100 Hz range. ANR headsets offer peak noise attenuation from about 70 Hz to around 150 Hz, depending on the manufacturer. While that works very well in a cockpit such as an average Cessna, Cirrus, Diamond, Piper or other makes, it doesn’t work well in an open cockpit. Open cockpits have noise in the higher frequencies as a result of wind flowing over the fuselage and wings, the bleat of the engine and wind swirling around you.

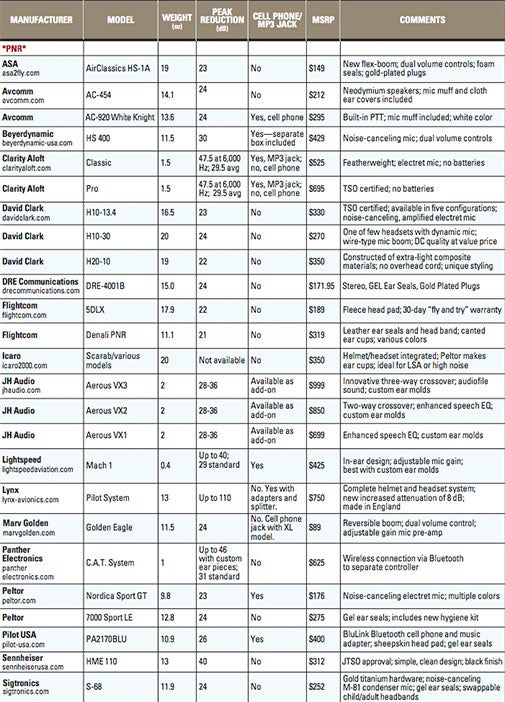

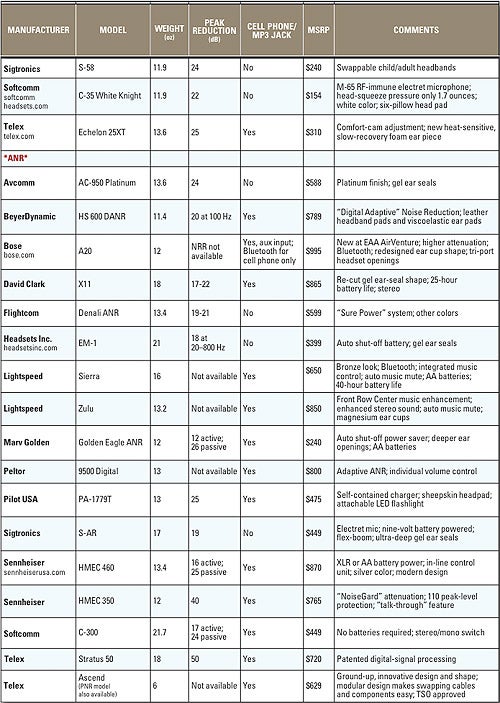

Careful attention to the noise curves supplied by manufacturers is important, as is a little education about how a headset works. By looking at the technical details and not relying strictly on marketing information, a pilot can make a better-informed decision on which headset to buy.

What To Look For

Headsets do two things: allow you to clearly transmit your verbal message and save your hearing. That’s it. Modern headsets have added goodies like the ability to connect your cell phone or MP3 player wirelessly via Bluetooth, or more comfortable head pads or lots of other things. But the basic role of the headset is to make transmissions clear and to block harmful noise.

Harmful noise has been defined by the Occupational Safety and Health Organization (OSHA) as any sound louder than 90 decibels (dB). The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) defines it as anything louder than 85 dB. Sounds at those thresholds cause permanent hearing loss; permanent as in “irreversible” and “incurable.” That’s why we pilots need to take headsets seriously.

Most pilots know that ANR headsets use active circuitry (hence the name) to block noise by generating a sound in the ear cups that’s acoustically “opposite” the noise, thus cancelling it out. Passive headsets (PNR) use foam, clamping force, ear cup design, ear seals and different materials to simply block harmful noise. ANR is best in cockpits where the low-frequency hum is present, which is in most GA airplanes. PNR is great where high- and midfrequencies are the offenders. Both block noise very effectively.

The microphone, as with my experience in my friend’s Decathlon, is critical but often overlooked. Pilots just take what they get with the headset. But pilots should know that there are options for better microphones. Without going into detail on the effects of impedance and gain, the important thing to remember is that you can replace the microphone on many models (not all) with one that puts out a stronger signal and rejects cockpit noise. Enhancements like the specialized windscreens and covers made by aftermarket retailers can make a dramatic difference in the quality of your transmissions.

Comfort is critical and not much needs to be said here, other than each person’s head is different and what I think fits nicely could be your medieval torture device. Trying headsets out is the name of the game, and air shows with manufacturer booths are great places to “look and feel.” Finally, look at the newer “in-ear” sets put out by several manufacturers. Though passive, many pilots say they’re quieter than ANR sets. They use tiny speakers that fit directly into the ear canal and offer amazing performance for their almost imperceptible weight.

Price shouldn’t always drive your purchase, though $75 eBay bargains should be suspect. I recommend going new instead of used since manufacturers always are improving their headset lines, and technology is moving faster than it ever has before. By defining your mission, educating yourself a bit and wading beyond the marketing hype, you can find the perfect headset for yourself—the one you’ll be happy to put on as soon as you step into the cockpit.