When the event first went public, the Air Force was swamped with nearly 2,500 applications, so a lottery was held. One hundred lucky pilots were invited to attend the civilian fly-in on Rosamond Dry Lake at Edwards Air Force Base. There were some restrictions on what could be flown in: no jets, ultralights, balloons or LSAs. But just about anything else was acceptable, and a wide range of aircraft, from warbirds to multi-engine pistons, singles and even a few aerobatic airplanes, made it safely to the parking area on the hard-packed mud. |

Sixty miles northeast of Los Angeles, restricted airspaces R-2508 and R-2515 cover Rosamond Dry Lake, home of Edwards Air Force Base. Made famous by the likes of Bob Hoover, Scott Crossfield, Glen Edwards, Pancho Barnes and scores of other test pilots, the Mojave Desert airbase is where Chuck Yeager first broke the sound barrier in the Bell X-1, and where the North American X-15 touched the edge of space, setting speed records that still stand today. It’s a place of military secrets, heroic saves, near-disasters and breakthrough technologies. And since the 1940s, when some of the most secret aerospace programs were developed, Edwards lakebed has been strictly off-limits to civilian pilots—until one day last October.

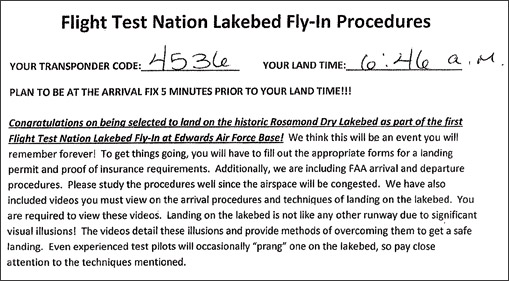

One hundred general aviation pilots were selected in a lottery to attend the Flight Test Nation Lakebed Fly-In on October 1, 2010, by being among the first private civilian aircraft to land on the lakebed. The morning sun was still below the horizon when we arrived at the designated holding area above Saddleback Peak, prior to our assigned arrival slot of 6:46 a.m. The air was smooth and clear, and we could spot airplanes orbiting everywhere—on the Avidyne moving map and out the window of a Cirrus SR22 that we had rented from Justice Aviation at Santa Monica airport.

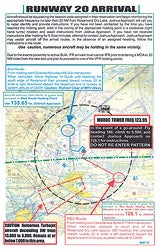

“November One Six Six Three Charlie. Fly heading 270. Vectors to the field. Maintain VFR. Altitude your discretion,” was Joshua Approach loud and clear through our headsets. It was the radio call we had been waiting for. We turned toward the south end of Rosamond Dry Lake and began a descent to pattern altitude of 3,300 feet. The 21-square-mile dry lakebed in the distance was hard to miss, and as we got closer we were able to discern runway 20, painted on the uniform tan surface. Air Force controllers standing in the back of a flatbed truck dubbed “Muroc tower” cleared us to land, and our wheels sank to greet the cracked desert.

|

Participants came from all over the country. One group had spent three days flying VFR from Colorado in a Cherokee, battling marginal weather the whole way. Another pilot flew his plane all the way to California from Connecticut. Throughout the event, the Air Force entertained everyone with a pancake breakfast, a display of historic aircraft—from a P-38 Lightning to a Ryan PT-22—and a sonic boom courtesy of an F-22 Raptor. Numerous briefings outlined the test flight mission, airspace safety, base history and collision avoidance. Major General David Eichhorn talked in some detail about the mission of the base and how flight testing makes the restricted airspace around Edwards extremely dangerous for any navigationally challenged GA pilot who might wander through.

programs were first developed, Edwards Lakebed has been off-limits to civilian pilots—until one day last October.

As the afternoon approached, so did the weather. Ominous storms moved in from the south, so an early departure briefing was held, and pilots were issued departure group numbers and start times. Each plane threw back clouds of dust as the power came up and they accelerated for liftoff. The foreboding weather provided a dramatic backdrop to a once-in-a-lifetime experience, and there’s no question that everyone left with a newfound appreciation for the hard work done by all the folks at Edwards.

|

Our Cirrus SR22 from Santa Monica’s Justice Aviation was one of the first to arrive to the fly-in on the lakebed. Out of 2,500 entries in the lottery held by Edwards AFB, only 115 civilian aircraft were selected to land on the dry lakebed within the restricted area. Those who weren’t picked were invited to drive in. Our Cirrus SR22 from Santa Monica’s Justice Aviation was one of the first to arrive to the fly-in on the lakebed. Out of 2,500 entries in the lottery held by Edwards AFB, only 115 civilian aircraft were selected to land on the dry lakebed within the restricted area. Those who weren’t picked were invited to drive in. |

Originally called Muroc Field, the airfield’s name was changed in 1949 to honor test pilot Glen Edwards after he was tragically killed in the famous Northrup flying wing bomber when it crashed during a test flight. The key mission of the base today is to evaluate aircraft and airborne weapons systems to ensure that they meet operational combat support and training requirements. The Edwards test airspace covers about 20,000 square miles that includes three supersonic corridors and four aircraft spin areas. Between the Rogers and Rosamond lakebeds there are runways of up to 7.5 miles in length—long enough to handle just about any emergency. Originally called Muroc Field, the airfield’s name was changed in 1949 to honor test pilot Glen Edwards after he was tragically killed in the famous Northrup flying wing bomber when it crashed during a test flight. The key mission of the base today is to evaluate aircraft and airborne weapons systems to ensure that they meet operational combat support and training requirements. The Edwards test airspace covers about 20,000 square miles that includes three supersonic corridors and four aircraft spin areas. Between the Rogers and Rosamond lakebeds there are runways of up to 7.5 miles in length—long enough to handle just about any emergency.

The original idea to hold a civilian fly-in was first presented by Flight Safety Officer Bill Koukourikos for the purpose of discussing airspace safety. In a general briefing for all participants, Koukourikos also provided tips for landing on a dry lakebed.

|

Midair Collision Avoidance

|

There are many areas of the country surrounded by military airspace—mostly in the form of MOAs, training areas, military training routes (MTRs) and restricted areas. VFR operations are allowed in and around many of these areas, but every pilot should recognize that operations in active military airspace are extremely risky. Remember that military training or flight test aircraft are probably moving at very high speed—often in excess of 500 knots. Studies have shown that if you’re on a collision course with a closure rate of 600 knots, there’s no way to avoid a collision if you see each other any closer than 1.5 miles apart. At that distance, you’re only nine seconds away from each other. Even if the military aircraft pulls 7 G’s and you pull your maximum rate turn away from each other, you’ll collide. Keep in mind that two miles is about the maximum distance where a typical GA aircraft can be spotted in ideal daylight conditions. That gives you only about three seconds to spot each other and do something about it. And don’t forget that some of the most modern military aircraft may not even have a pilot on board. This is an issue to take seriously, and the Air Force provides some good safety tips: There are many areas of the country surrounded by military airspace—mostly in the form of MOAs, training areas, military training routes (MTRs) and restricted areas. VFR operations are allowed in and around many of these areas, but every pilot should recognize that operations in active military airspace are extremely risky. Remember that military training or flight test aircraft are probably moving at very high speed—often in excess of 500 knots. Studies have shown that if you’re on a collision course with a closure rate of 600 knots, there’s no way to avoid a collision if you see each other any closer than 1.5 miles apart. At that distance, you’re only nine seconds away from each other. Even if the military aircraft pulls 7 G’s and you pull your maximum rate turn away from each other, you’ll collide. Keep in mind that two miles is about the maximum distance where a typical GA aircraft can be spotted in ideal daylight conditions. That gives you only about three seconds to spot each other and do something about it. And don’t forget that some of the most modern military aircraft may not even have a pilot on board. This is an issue to take seriously, and the Air Force provides some good safety tips:

⢠Squawk a transponder code. That will allow controllers and military pilots to more easily see you on radar. Advertisement

To learn more, Edwards offers a wealth of valuable information and safety tips at: www.edwards.af.mil/library/flightsafety. |