|

Yes, I know. There aren’t many of those procedures in use, and even when they’re available, controllers are more likely to issue a circle-to-land clearance on the standard localizer/ILS.

Still, they’re a nuisance we’re sometimes forced to deal with. It’s so simple and logical to fly into the needle that pilots are nonplussed at the thought of flying the needle “backward.” In every other variety of instrument procedure, the pilot corrects into a diverging needle—needle left, correct left, needle right, correct right. Even on an NDB approach (assuming the station is still in front of the aircraft), the pilot flies the head of the needle, and corrects left for left, and vice versa.

Pound that message into a pilot’s head a few thousand times during private, commercial and instrument training, then see what happens when sensing becomes reversed.

Back-course (BC) localizer approaches subject a pilot to reverse needle indications on the OBS. You fly right to correct left and versa vicea, counterintuitive to pilots who have been taught that you always fly into the needle.

Fortunately for those pilots who use the airspace regularly for business and pleasure, BC approaches are rare, and that’s understandable. Whenever possible (barring complaints from the neighbors under the proposed approach path), airports lay out their runways into the wind. Geographic and political features sometimes make that impractical, but most of the time, runways are oriented to allow pilots to benefit from some slight headwind on landing.

Similarly, the prevailing ILS is typically oriented to the longest runway. The implications for instrument students should be obvious. It’s almost impossible to practice back-course approaches, because you’re most often flying directly into the flow of traffic coming off the most active runway.

For better or worse, I had a back-course approach in my backyard when I was working on my instrument rating in the ’70s. I learned to fly in the Los Angeles Basin, good news and bad news, depending upon your point of view. Then, as now, LA was one of the world’s busiest areas for air traffic, especially general aviation. At one time in those questionably halcyon days, the Los Angeles Basin owned four of the 10 busiest airports in America: LAX, Van Nuys, Long Beach and Torrance. The last three were predominately reserved for light aircraft, though Long Beach did have some airline operation. Collectively, there were something like 18 airports crammed into a fairly small area. In short, Los Angeles airspace was (and still is) very busy.

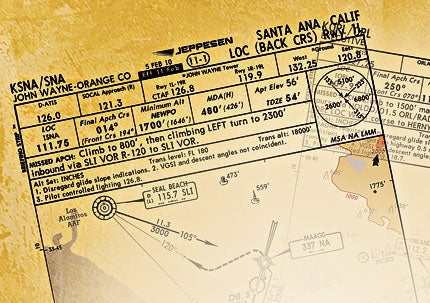

The good news was that you could find practically any kind of approach you could imagine, and the Orange County back course was one of them. My instructor made it a point to insist one morning that we be in position to shoot the runway 1 back course to Santa Ana, Calif., at sunrise, the very moment the airport opened for business and a half hour before the parade of airline 737s began departing and arriving. Fortunately, there were no other idiots up that early, so we were able to get in two practice back-course efforts to missed approaches before the tower shooed away our little Skyhawk.

The better news is that it’s equally difficult for an examiner to gain access to a real, live back-course approach (unless they’re willing to conduct his examination at 6 a.m.), so most of the time, you shouldn’t have to worry about demonstrating your proficiency.

Right up front, it’s important to acknowledge that pilots flying behind HSIs have an advantage on back-course approaches. All the old analog HSIs and the current crop of digital, glass-panel-equipped airplanes, whether Garmin, Avidyne, Aspen, Sandel or some other manufacturer, have made BC approaches less of a problem. You simply set the front course heading under the pointer, and all will be forgiven. The OBS will deliver proper sensing with left for left and right for right.

In the case of the aforementioned Orange County approach, you’d simply set the front-course localizer heading of 193 degrees on the HSI, and fly the 013 degree radial just as if it was a front-course localizer. Corrections would all be normal, i.e. in the direction of needle deflection.

You might think experienced pilots could easily force their brains to overcome the puzzle of reverse sensing. Not necessarily. A large accumulation of hours doesn’t immunize pilots to the confusion of BC. Years ago, a retired U.S. Navy fighter pilot was flying his Bonanza into Monterey, Calif., in hazy VFR conditions, and decided to simply track the back course to the proximity of the airport from the southwest until he was in close, then join the normal pattern. Like most of us, he had read about back-course approaches but never actually flown one. After a confusing series of S-turns, he gave up and followed the coastline to Monterey.

Some pilots who must fly BC approaches on a regular basis claim that a rote technique serves them as well or better than any other method. I was first exposed to that philosophy in amphibious seaplane training at the Lake Aircraft facility in Tomball, Texas. We were taught to say out loud, “This is a water landing—the wheels are up,” or “This is a land landing—the wheels are down.” The theory was/is that it’s difficult to ignore your own voice suggesting the proper action. (The philosophy is somewhat analogous to a memory trick for remembering someone’s name. Use a weird voice and shout it out loud, preferably when there’s no one around, to call the guys in white coats.)

Accordingly, pilots faced with an off-course deviation during a back-course approach may say out loud, “The needle is left, fly right,” or “The needle is right, fly left,” or words to that effect.

IFR minimums for back-course approaches typically are about the same as for circling approaches following a precision ILS. At Orange County, ILS minimums on 19R were 200-feet ceiling and 2,400-feet RVR with all approach facilities working. Switch to a localizer with the glideslope generator inop, and minimums became 408 feet and 2,400 RVR. Convert the approach to a circling, however, and minimums rose to 600 and a mile. In this case, VOR and NDB minimums were the same as the bottom numbers for the back course at Orange County.

That won’t always be the case. Terrain and noise considerations may dictate a higher minimum for a back course than the other approaches.

In addition to higher minimums, back- course approaches come with a few other built-in disadvantages besides reverse sensing. Perhaps because the back course is rarely used, airports are reluctant to spend money installing markers or compass locators. Accordingly, you can expect most localizer back-course final approach fixes to utilize intersections with a nearby VOR rather than NDBs or outer markers.

Timing an approach from an intersection can be less precise than from a beacon, depending upon the accuracy of your number-two nav. For that reason, it’s perhaps more important to descend to the MDA early and be set up for a miss if the airport doesn’t appear in the distance, rather than make a gradual descent to arrive at the missed approach point exactly when the time expires. Also, keep in mind that needle swings with reverse sensing are liable to become very squirrelly as you approach the airport and localizer tolerances become finer.

Standard advice for instrument flight goes double during back-course approaches. Just as with a normal front-course localizer, the trick when off-course is to make a heading change, HOLD IT and watch for a needle reaction before re-correcting; then, correct again if necessary. Don’t chase the needle with continuous corrections, or you may wind up prescribing a series of S-turns down final. By reason of the inherent confusion caused by reverse sensing, a back course can get away from you more quickly than you’d believe possible.

To minimize confusion, some instructors suggest making fewer corrections, and then only after major needle deviations. Another trick is to join the BC localizer as far outside the FAF as possible (if you have the option) to help accustom your brain to reverse sensing.

Flying a back-course approach only serves to reinforce the suggestion that pilots should fly specific headings during instrument flight rather than correct “a little to the right (left).” Rather than choose to correct five degrees left, pick a specific heading that’s five degrees from your current direction, and think that number.

There’s such a thing as a precision back-course approach in the form of a back-course ILS. You may even run across a BC ILS with accompanying DME, or you can sometimes create your own on airports with collocated VORTACs. (Dial up the VOR until distance information appears, select DME, hold and switch to the ILS frequency.)

Back-course approaches typically carry minimums near or right at those of a front course, but a smart pilot will add a fudge factor of at least 100 feet. Trying to fly a glideslope needle normally and a localizer backward is a trick that deserves practice.

Sadly, true practice may be difficult or impossible in the real world. There’s frequently no efficient method of practicing back-course approaches, at least not in an actual airplane. As mentioned above, there may not even be a BC approach within several hundred miles of your location, and if there is, ATC may be reluctant to allow you to fly it, as by definition, it will be directly into the flow of traffic.

The only logical alternative is a simulator, and that’s a viable method of familiarizing yourself with a back-course approach, certainly one of the most unusual and least popular of IFR- approach procedures.