|

Early in September of 1977, a fellow Alaska registered guide asked me to fly some avgas to a hunting camp he operated on the west side of the Alaska Range. On the morning of September 7, I loaded my bigfoot Super Cub and lit out for Merrill Pass and the Stony River country beyond. It was just another trip with an airplane crammed full of avgas cans and crates.

Three hours and 45 minutes after liftoff from Anchorage’s Merrill Field, I lined up on the guide’s invisible tundra strip for the landing. Big tundra tires don’t leave much of a track in Alaska’s vast bush country, and if I hadn’t known where the guide’s camp was, I would never have found it. I off-loaded the avgas and cached it for future use.

The days are short, and quickly getting shorter, in Alaska’s September. It was nearly dark as I readied my Super Cub for the return. It also had started raining.

I had filtered some of the guide’s canned avgas into the Cub’s tanks, closely calculating the required quantity. My Super Cub had a vernier mixture control and an EGT gauge, so I could lean the fuel/air mixture with considerable accuracy. I took from the guide’s avgas cache only what was necessary to make the safe flight back to Merrill Field that night. I carried no reserve fuel.

I took off and climbed out to take up a straight-line course for the mouth of the pass, but darkness and rain had reduced visibility so I had to give up on that plan right away. I began following the Stony River’s meandering route upstream. The river was all I could make out on the ground. Getting myself as comfortable as possible in the cramped front office of the little Super Cub, I began to unscrew the mixture control, watching both the river and the EGT. The control was threading its way out, but the EGT was showing no change. I had already turned the red control knob enough to create at least some increase in exhaust gas temperature, but—fat, dumb and happy—I continued to unscrew the maddeningly ineffective thing. Suddenly, the whole assembly came off in my hand! The bolted connection at the carburetor had failed. I was without any mixture control at all. Without that leaner mixture, I was in really hot water.

Merrill Pass is unfriendly. Many Alaska pilots won’t fly it even on sunny days. It isn’t really as bad as it sounds, but in the dark of a rainy Alaska night, it isn’t a very cheerful place. Still, I was committed. In the dark, I could neither return to nor land at the guide’s invisible strip. Only an engine failure would force me to use a Stony River sandbar at night. I would have to punch on through the pass, weighing my options after I had reached the east end over long Chakachamna Lake. From there, it’s pretty much downhill.

After passing tiny Two Lakes, I could barely see the canyon that would signal the climb from 1,200 feet MSL to the necessary 2,400 feet that would see me over the very narrow rock saddle of the pass. I was so busy looking out under each wing that the rain-streaked windshield didn’t bother me at all. I had made more than 60 trips through this pass. But with peaks rising to 8,000 just off either wing, slopes too steep to support vegetation and the volcanic cone of Mount Spurr rearing up 11,000 feet dead ahead, I wasn’t as comfortable as I would have been during a daylight flight. I knew that I had enough fuel to get me through the mountains and out to the Big Susitna River delta before things would go south on me. The 20 minutes beyond were in serious doubt.

|

The pass is much too narrow to consider turning around inside, even with a Super Cub. Once in, your options are reduced to going on thru or landing steeply uphill and straight ahead. With boulders half the size of modest homes, such a landing would be a bad one. The only option is simply to fly on through the steep pass.

I crossed the saddle at about 20 feet, rolled into a right 45 degrees over the skeleton of an old military aircraft, and began a slow, descending left turn through the curving little valley that opened onto 20-mile long Chakachamna Lake, six minutes ahead and 1,300 feet below me.

When I reached the east end of Chakachamna, I called Anchorage radio for information on the oil exploration strip lying 15 degrees to my right and 25 minutes ahead. It was unpaved and unlighted, but it seemed a whole lot better than running out of fuel over the deadly waters of Cook Inlet or Knik Arm that feeds it. The strip was a generous 5,000 feet long. I could yawn and ho-hum through a night landing there. Anchorage radio was discouraging about permission for a landing at Beluga, the private strip in question, so I asked for vectors and straight-line distances to the nearest runway threshold at both Merrill Field and Anchorage International Airport.

Merrill Field was a few miles farther, but a beeline for that field would place me over cold water for only about 21â2 miles. If the engine finally starved out at that point, I could glide to dry land. I chose Merrill, which also gave me several emergency landing options that looked survivable. If I could just coax the thirsty Cub that far…

I had long before throttled back to best glide speed plus five, trying to stretch my fuel load as far as it would go. The slower airspeed was maddening but necessary. I needed maximum distance in the air under power. I wasn’t interested in being in the air without power.

I punched up Approach Control, advised them of my low-fuel situation, and requested whatever help they could give me. They approved a straight-in approach to Merrill Field’s runway 6, which would save me some air time by avoiding pattern entries and turns. It also would carry me over the major portion of the city of Anchorage, which I didn’t like. I went feet wet at 2,000 feet and throttled back for the long straight-in.

I landed short, took the first available right and taxied to the gas pumps. The engine was still purring along, but I didn’t know how.

The Cub’s tanks held a meager 38 gallons when topped off to the filler necks. Not all of that is usable. The meter at the pump read 39.6 after I had finished topping both tanks. Maybe I had larger tanks by a fat gallon. Maybe the pump wasn’t as accurate as it might have been. I couldn’t have cared less. I would have paid $20 a gallon for all 39.6 gallons right then.

I tied the little Cub down, gave her one last affectionate pat, and headed home for a hot shower, a warm dinner and a dry bed. Oh, yeah—I fixed that broken mixture control problem before the next flight. Flying full-rich isn’t my preferred method of engine management, even at sea level, much less through dark and rainy Merrill Pass.

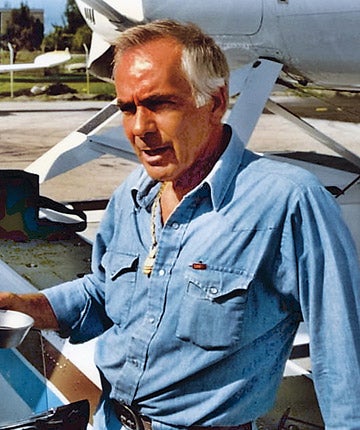

Raised in the hills of southeastern Ohio, where hunting and fishing were activities performed for the table rather than sport, Mort Mason honed those outdoor skills that would later be the foundation for his profession as an Alaska Registered Guide. Transferred to Alaska by the USAF, he realized that outdoor pursuits in the huge state without a roadway system required airplane travel. Buying his own airplanes and using his guiding skills to earn their keep, Mort has never looked back.