Misfueling occurs when the wrong type of fuel is pumped into an aircraft’s tanks. It could be that jet fuel gets pumped instead of gasoline, gasoline instead of jet fuel, automotive gas instead of aviation gas, automotive gas containing ethanol instead of auto gas with no additives, or something else yet to be devised by a creative fueling person.

Misfueling occurs when the wrong type of fuel is pumped into an aircraft’s tanks. It could be that jet fuel gets pumped instead of gasoline, gasoline instead of jet fuel, automotive gas instead of aviation gas, automotive gas containing ethanol instead of auto gas with no additives, or something else yet to be devised by a creative fueling person.

Recently, the misfueling issue attracted attention because of an accident that occurred on March 2, 2008. Shortly after taking off, a single-engine Cirrus SR22-G3 Turbo crashed into the upper floors of a condominium building in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. All four people on board were killed. The SR22 was marked with the word “Turbo,” referring to its turbocharged engine. Preliminary information indicated that the lineman who fueled the airplane has mistakenly interpreted the word “Turbo” to mean that the airplane was powered by a turbine engine. Therefore, he fueled the airplane with Jet A.

In a 1998 advisory circular, the FAA suggested that turbocharged aircraft owners remove any decals from the fuselage stating “Turbo” or “Turbocharged.” In the past, these markings have given the wrong impression to inexperienced line personnel.

Misfueling first attracted real attention back in 1970 when a twin-engine Martin 404 with two pilots, two cabin attendants and 29 passengers crashed shortly after departing from DeKalb-Peachtree Airport in Atlanta, Ga. The airplane was carrying approximately 800 gallons of fuel. The weather at the time was 400 feet overcast; visibility was one mile in light rain and fog. During climb, there was a loss of power from the #2 engine; the pilots suspected carburetor icing. While they were trying to restore the #2 engine, the #1 engine lost power. The flight crew declared an emergency and reported that they were going down. The departure controller gave them a vector toward Atlanta International Airport, seven miles away, for an emergency landing. As the airplane glided below the overcast layer, the pilot noticed an interstate highway and decided to land on the median strip. The airplane struck a car, killing all five people inside, and struck the side of a highway bridge were it came to a stop. There were no on-board fatalities. The NTSB found that, rather than 100-/130-octane avgas, Jet A had been pumped into the airplane. The investigation concluded that the two linemen who had refueled the airplane hadn’t received formal training. Both said they knew they were putting Jet A into the tanks and had previously refueled Martin 404 airplanes with that fuel. (As it turned out, those particular 404s had been fitted with turboprop engines, not piston gasoline engines as in the accident airplane.) The accident airplane didn’t have decals at the fueling ports to indicate the type of fuel it used. As a result of this accident, the NTSB recommended that the FAA require placement of a colored circle—corresponding to fuel color—around each fueling port. The NTSB also recommended that each fueling nozzle be marked with the appropriate fuel color.

In 1975, the FAA proposed mandating just such a color-coding system. It included a requirement that no person may operate an aircraft unless it has been determined that it received the proper fuel type. The FAA withdrew its notice of proposed rulemaking after receiving more than 400 negative comments from several airlines and such groups as AOPA, EAA and NBAA. The system did, however, take hold on a voluntary basis.

When a gasoline engine is exposed to Jet A at takeoff power, detonation, high cylinder-head temperatures, loss of power and complete engine failure occur. The effects of Jet A in the tanks won’t be apparent until residual gas in the fuel system has been drawn through. Unless there’s been a long run-up and hold, this tends to coincide with takeoff. Interestingly, in an emergency, most turbine engines can run on gasoline for a limited time. If a jet aircraft is operated on gasoline, any run time should be logged in the maintenance record, and the fuel system should subsequently be purged.

In 1982, after investigating 13 more accidents where jet fuel was inadvertently used (resulting in 11 fatalities and nine serious injuries), the NTSB proposed that the industry develop a system to physically prevent jet-fuel nozzles from fitting into avgas tanks. Ideally, the physical differences would be maintained throughout the distribution chain.

In 1987, after investigating 19 accidents involving Piper PA31, Gulfstream Commander and Cessna 300/400 airplanes, the NTSB asked the FAA to issue an airworthiness directive requiring that those airplanes be fitted with port restrictors so that jet-fuel nozzles couldn’t be put into gasoline filler ports. The NTSB noted that PA31 Navajo (piston) and PA31 Cheyenne (turboprop) models look very similar.

The NTSB reported on a Canadian DC-3 cargo plane that crashed during its third attempt to take off from St. Louis, Mo., en route to Toronto, Canada, on January 9, 1984. After the second aborted takeoff, the pilots radioed the FBO to ask what type of fuel was put in the tanks. They were told that it was 100LL. On the third takeoff try, both engines lost power just as the landing gear was retracted. After the left wing hit a utility pole, the aircraft went through a fence and hit a highway embankment. The captain was killed; the first officer received serious injuries. The airplane had been serviced with Jet A.

Also in 1984, a Cessna 402C operated by Provincetown-Boston Airline was taking off from Naples, Fla., on a Part 135 commuter flight. Night visual conditions prevailed. Just after takeoff, both engines quit, so the pilot executed a forced landing to a field. The aircraft was destroyed by the impact and a postcrash fire. One of the five passengers was killed. The NTSB reported that the aircraft had been refueled with Jet A instead of avgas. The Jet A fuel truck was parked where the 100LL fuel truck was usually parked. A lineman had accidentally used the Jet A truck, which was identical to the avgas truck, but for the decal used to identify carried fuel type. The investigation found that the lineman’s training consisted of just 30 minutes of reading the company’s maintenance manual on how to refuel different company aircraft.

By 1985, U.S. manufacturers voluntarily adopted standards for filler-port sizes on piston and turbine airplanes. Under the standards, the port on an aircraft’s gas tank had a maximum opening diameter of 2.36 inches. The spout on a gasoline nozzle had a maximum outside diameter of 1.93 inches. A port for a turbine fuel tank had a minimum opening diameter of 2.95 inches. Operators of gas-powered piston airplanes with tank openings bigger than the new industry standards were urged to install restrictors, which reduce the diameter of the tank opening, making it impossible to insert a jet-fuel nozzle into an avgas filler port. This installation could be done by any pilot/owner as part of preventative maintenance.

A newer fueling port for aircraft requiring Jet A is almost rectangular in shape, but with slightly rounded sides, measuring about 2.90 inches long by 1.40 inches wide. A newer Jet A nozzle, measuring 2.66 inches long by 1.13 inches wide, is designed to fit either old or new filler ports. The redesign was made bearing in mind that diesel-equipped airplanes may one day become a significant part of the fleet. Because a single-engine Cessna equipped with a diesel engine requiring Jet A could look virtually identical to a gas-driven model, the change in shape from classic, round tank ports seemed prudent.

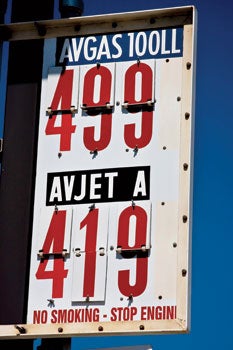

No matter what steps manufacturers, fuel distributors or government agencies may take, the last line of defense against misfueling remains with the pilot. If using a self-serve pump offering a choice of fuels, make sure that you have correctly followed the selection procedure. Look for appropriate color coding and placards on the dispensing equipment and the aircraft. When placing a fuel order with an FBO, make certain there’s no question about the fuel type you’re ordering. Make every effort to be at the aircraft when the fuel is pumped. Check fuel samples. Jet fuel will leave a greasy spot on a clean piece of paper.

Being on hand for refueling might have made a difference for the pilot of a Beech B60. On August 1, 2007, the pilot called an FBO at Bismark, S.D., to pull out the airplane and add 30 gallons to each side. When the pilot arrived at the airport, the airplane had been refueled. During his preflight inspection, the pilot looked in the fuel tanks, and the liquid appeared to be blue, consistent with 100LL avgas. He subsequently started up, taxied and did pretakeoff checks; everything seemed normal. During the initial takeoff roll, the left engine “stumbled,” so he aborted and returned to the maintenance area where a mechanic came on board and performed a full power run-up. Everything seemed normal, so the mechanic left and the pilot taxied out again. After receiving a clearance for takeoff, he taxied onto the runway, held the brakes and set power to 35 inches of manifold pressure. Everything seemed good, so he applied full power and released the brakes. After liftoff, the pilot noticed a fluctuation in the manifold pressure on the right engine. He began a slight left turn. Then, the manifold pressure and fuel flow indications for both engines began to fluctuate. The pilot was unable to do anything about the power fluctuations and decided he’d better get down. The pilot had to maneuver to avoid trees, cars, houses and people before making an off-airport landing. The pilot escaped injury. A fuel receipt at the FBO revealed that the airplane had been refueled with jet fuel instead of gasoline.

Peter Katz is editor and publisher of NTSB Reporter, an independent monthly update on aircraft accident investigations and other NTSB news. To subscribe, write to: NTSB Reporter, Subscription Dept., P.O. Box 831, White Plains, NY 10602-0831.