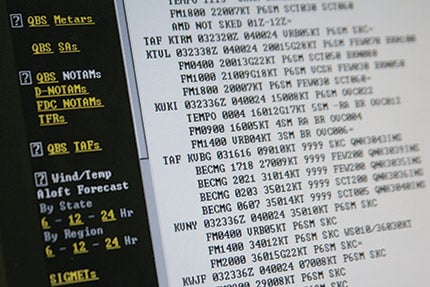

There’s never been so much pre- and in-flight weather information available for pilots. If you can’t gather the raw data, forecasts and current airport observations by yourself, a briefer at a Flight Service Station (FSS) can do it for you. Unfortunately, some pilots continue to experience trouble applying the wealth of data and meteorological analyses to the realities of flight. Investigators often find that clues about what a flight would later encounter were readily available in a preflight weather briefing. In some cases, the pilot being briefed seemed to show an understanding of what he or she was being told, yet the import didn’t register. Earlier this year, the NTSB finished investigating some accidents involving weather encounters.

There’s never been so much pre- and in-flight weather information available for pilots. If you can’t gather the raw data, forecasts and current airport observations by yourself, a briefer at a Flight Service Station (FSS) can do it for you. Unfortunately, some pilots continue to experience trouble applying the wealth of data and meteorological analyses to the realities of flight. Investigators often find that clues about what a flight would later encounter were readily available in a preflight weather briefing. In some cases, the pilot being briefed seemed to show an understanding of what he or she was being told, yet the import didn’t register. Earlier this year, the NTSB finished investigating some accidents involving weather encounters.

At 9:04 p.m. on February 16, 2007, a Cessna 340A crashed 3 nm south-southeast of Council Bluffs Municipal Airport (CBF) in Council Bluffs, Iowa. The Part 91 business flight was operating on an IFR flight plan; night instrument meteorological conditions prevailed. The pilot and all three passengers were killed. The flight left Northwest Arkansas Regional Airport in Fayetteville, Ark., two hours prior to the crash. Earlier that day, the aircraft flew from CBF to Jasper County Airport (JAS) in Jasper, Texas, with an intermediate fuel stop at Fort Smith Regional Airport in Fort Smith, Ark.

Investigators determined that an FSS weather briefer had informed the pilot that the flight might encounter moderate icing conditions and turbulence. The 1977 Cessna 340A was equipped with inflatable deice boots to provide in-flight icing protection. Knowing this, it’s possible that the pilot discounted the importance of the icing forecast.

The first leg of the return flight departed JAS at 5:29 p.m., stopped at Fort Smith for fuel and then departed for CBF. At 8:43:56 p.m., the flight established radio contact with Omaha Terminal Radar Approach Control (TRACON), and the pilot reported that the airplane was level at 11,000 feet. The flight was cleared to descend, at the pilot’s discretion, to 5,000 feet and proceed to the Omaha VOR. The pilot requested the VOR-A approach into CBF. The controller told the pilot about reports of light to moderate icing below 9,000 feet, and cleared the pilot to maintain 3,000 feet until established on the approach. At 8:55:34 p.m., the pilot leveled at 3,000 feet, at which time the aircraft was 15 miles south of the airport. The controller released the pilot to CBF’s CTAF at 8:58:20 p.m.; the flight was 10 miles south of CBF at that time. No further communications were received from the airplane.

The pilot held an ATP certificate with single-engine and multi-engine land ratings. He had a flight-instructor certificate with single-engine, multi-engine and instrument ratings, as well as a ground instructor certificate with an advanced rating. The pilot’s first-class medical certificate had no restrictions or limitations. Investigators determined that the pilot had accumulated about 3,275 hours of total flight time.

Weather conditions recorded shortly after the accident by CBF’s AWOS, located about three miles north of the accident site, indicated wind from 330 degrees at 25 knots, gusting to 36 knots; visibility at ¾ mile in unknown precipitation; an overcast cloud ceiling at 1,000 feet AGL; temperatures of minus-1 degree C; a dew point of minus-3 degrees C; and altimeter at 29.61.

An AIRMET issued five hours before the accident warned of moderate turbulence below 18,000 feet, with conditions ending in the vicinity of the accident site around the time of the crash. The AIRMET also warned of the potential for low-level wind shear, with conditions continuing well beyond the time of the accident. Another AIRMET noted the possibility of moderate icing below 16,000 feet until 1:00 a.m. National Weather Service data indicated that the probability of icing increased between 9,000 feet and 3,000 feet, with a greater than 70% probability of icing conditions. The data was consistent with a high probability of moderate to likely severe icing conditions in the area of the accident.

The NTSB determined that the probable cause of the accident was the pilot’s continued flight into adverse weather, and his failure to maintain altitude during the instrument approach. Contributing factors were the presence of severe icing, moderate turbulence and low-level wind shear.

At 9:10 a.m. on April 21, 2007, a twin-engine Piper PA23-250 crashed into the Atlantic Ocean, about 26 miles east of Fort Lauderdale, Fla. Instrument meteorological conditions prevailed; a VFR flight plan had been filed for the Part 91 flight from Fort Lauderdale Executive Airport (FXE) to Fresh Creek Airport (YAF) on Andros Island, Bahamas. The airplane was destroyed and the certificated private pilot and the four passengers were killed.

The pilot phoned Miami Automated International FSS and advised that he would be departing for YAF from FXE at 9:00 a.m.; he requested a weather briefing and said that he would file a VFR flight plan. The briefer reported that the remains of a low-pressure disturbance were in the area of the Northern Bahamas and some showers were present along the coast of Florida as far north as Titusville and as far south as Biscayne Bay. The weather was moving to the south and, locally, there were some heavy returns. The NTSB didn’t report whether the pilot had any sort of access to weather radar visuals, either directly via computer or by glancing at a television airing local weather. A visual depiction would likely have had a greater impact on the pilot than the verbal description provided by the briefer. The airplane wasn’t equipped with radar or Stormscope.

At 8:48 a.m., the pilot contacted the FXE clearance delivery controller, requesting VFR flight following to YAF at 7,500 feet. The pilot was cleared to maintain VFR conditions and to fly an east departure from FXE. At 8:50:31 a.m., the pilot contacted the FXE ground controller and was cleared to taxi to runway 08. At 8:56:10 a.m., the pilot was cleared for takeoff and subsequently handed off to Miami Departure Control. The pilot was instructed to maintain VFR conditions at or below 3,000 feet. Later, the pilot was told to contact Miami Approach by the Fort Lauderdale North controller. This controller also told the pilot to maintain VFR conditions at or below 3,000 feet. At 9:01:38 am., the controller cleared the pilot to fly a course heading of 130 degrees, then cleared the pilot for a VFR climb and requested his final altitude. After acknowledging, the pilot said he was going to stay around 2,500 feet because of some weather in front of him.

At 9:04:03 a.m., the pilot attempted to contact the Miami North Approach controller, stating he was at 3,200 feet. The controller didn’t respond and, at 9:07:08 a.m., the pilot again attempted to contact the controller, stating he was at 4,000 feet, climbing to 7,500 feet. The controller responded and gave the pilot the current altimeter setting, which the pilot acknowledged. That was the last transmission from the pilot, and the flight was subsequently lost from radar contact. Search-and-rescue operations began, and at 10:45 am., a U.S. Coast Guard helicopter crew located a debris field on the ocean about three miles north-northwest of the flight’s last radar position. By the time a Coast Guard ship arrived at the site, the debris field had broken up and nothing could be recovered.

The pilot held a private pilot certificate with single-engine and multi-engine land ratings; he didn’t have an instrument rating. His FAA third-class medical certificate was issued with no limitations. The pilot’s logbook couldn’t be located, but investigators learned that the pilot had slightly more than 200 total flight hours.

The pilot owned the accident airplane, which hadn’t had an annual inspection within the preceding 12 months. The last altimeter and airplane static system test was performed on March 6, 2000. FAR Part 91.411 requires the test every 24 months in order for the airplane to be certified for IFR operations. The last transponder system test was also performed on March 6, 2000. FAR Part 91.413 requires the test every 24 months in order for the airplane to be certified for IFR operations or in airspace where a transponder is required. The Miami Doppler weather radar image at 9:18 a.m., overlaid with Miami Approach radar data for the accident flight, depicted the flight track of the airplane departing FXE east-southeast into a line of level 4 thunderstorms that would be expected to contain severe turbulence with lightning. The Miami Doppler image at 9:24 a.m. depicted “intense” echoes within one mile of the flight path, consistent with level 4 and 5 thunderstorms that would probably contain severe turbulence, lightning, hail and organized surface wind gusts.

The NTSB determined that the probable cause of this accident was the pilot’s continued VFR flight into known adverse weather conditions, resulting in an in-flight loss of aircraft control. Contributing to the accident were thunderstorms.

Peter Katz is editor and publisher of NTSB Reporter, an independent monthly update on aircraft accident investigations and other NTSB news. To subscribe, write to: NTSB Reporter, Subscription Dept., P.O. Box 831, White Plains, NY 10602-0831.