Inflight Medical Crisis: Who Makes The Call?

How a real inflight medical emergency unfolds

I'm tooling around at 37,000 feet the other day---minding my business with 175 peeps comfortably lost in their own personal 2 square feet---when I overhear my lead attendant making an announcement seeking medical assistance. I tap my copilot on the shoulder and signal to him---picture a monkey see, monkey do routine---to listen in on the intercom. He hears the last strains of the announcement, turns off his cabin intercom switch, says, "Glad you're the captain," and returns to his distance learning.

I return to my thoughts and gaze out to the Colorado skies and mountains beneath, knowing this development moving 500 mph behind me will soon become my focus. I ponder my half-eaten salad perched precariously on my lap, supported by the aircraft logbook. So far so good; the logbook seems to have snared any flying food. "Do I finish this now or set it down to enjoy later?" I ask myself, realizing that some law of nature connects the former choice to interruption, dead ahead. I grab the fork again.

"CHIME CHIME!"

I feverishly chew on the romaine smothered in ham, bacon and boiled eggs while connecting to the intercom and answer, "Hawoh?"

Silence.

"Is this the captain?"

I swallow. "Yes, what's up?" I answer, knowing that 99 percent of inflight medical situations resolve themselves without any intervention from the cockpit. The attendants are adept at securing medical assistance in the cabin or using their own training. Making an unscheduled landing for medical reasons is a rare bird.

"We have a 16-year-old girl laid out on the floor, and a nurse and an EMT attending to her. She's experiencing chest pains, and the nurse says that YOU should probably land."

I let that last remark go. The airlines all have contracted medical advice via a two-way radio network, and it is that doctor alone, some anonymous voice over the radio, that makes the call to divert or press on. I'm told he's paid more when the flight continues to the original destination. I digress.

"Thank you for the information, and we will get you a doctor on the radio. Give me a couple minutes."

The cabin of the aircraft has a connection port that allows the attendants or medical professionals to communicate directly with the doctor, while we listen in up front.

"CHIME. CHIME." They are calling me again.

"Yes?"

They need the doctor now. The girl is 16, taking birth control and antibiotics for a UTI, has tingling, and chest pains. That has all been recently revealed---in front of her mother, who's no doubt hovering nervously over her. The deeper moral implications of all this adds unusual intrigue.

"Okay, give me one second, I can't get ahold of the doctor until I hang up with you." My copilot is monitoring ATC frequencies and flying the aircraft, and I'm trusting him implicitly to keep us all safely on course---I'm a little distracted. He has dialed into radio number two the frequency that our dispatch paperwork says should connect us to doctors in this part of the world.

I call out on the frequency several times and hear nothing back. Of course. I smile because even during a worst-case simulator scenario---when everything isn't working right, even then---the instructor will play along and concede you've dialed in the appropriate frequency for outside assistance.

"CHIME. CHIME!!"

"We've almost got the doctor online, standby one minute."

"The EMT and I think we should land now!"

That's a new one. I've never been ordered to land by a flight attendant. Not even during a simulator check-ride.

"Excuse me? I don't think that's our decision to make. The doctor will be online shortly." I hope that is true.

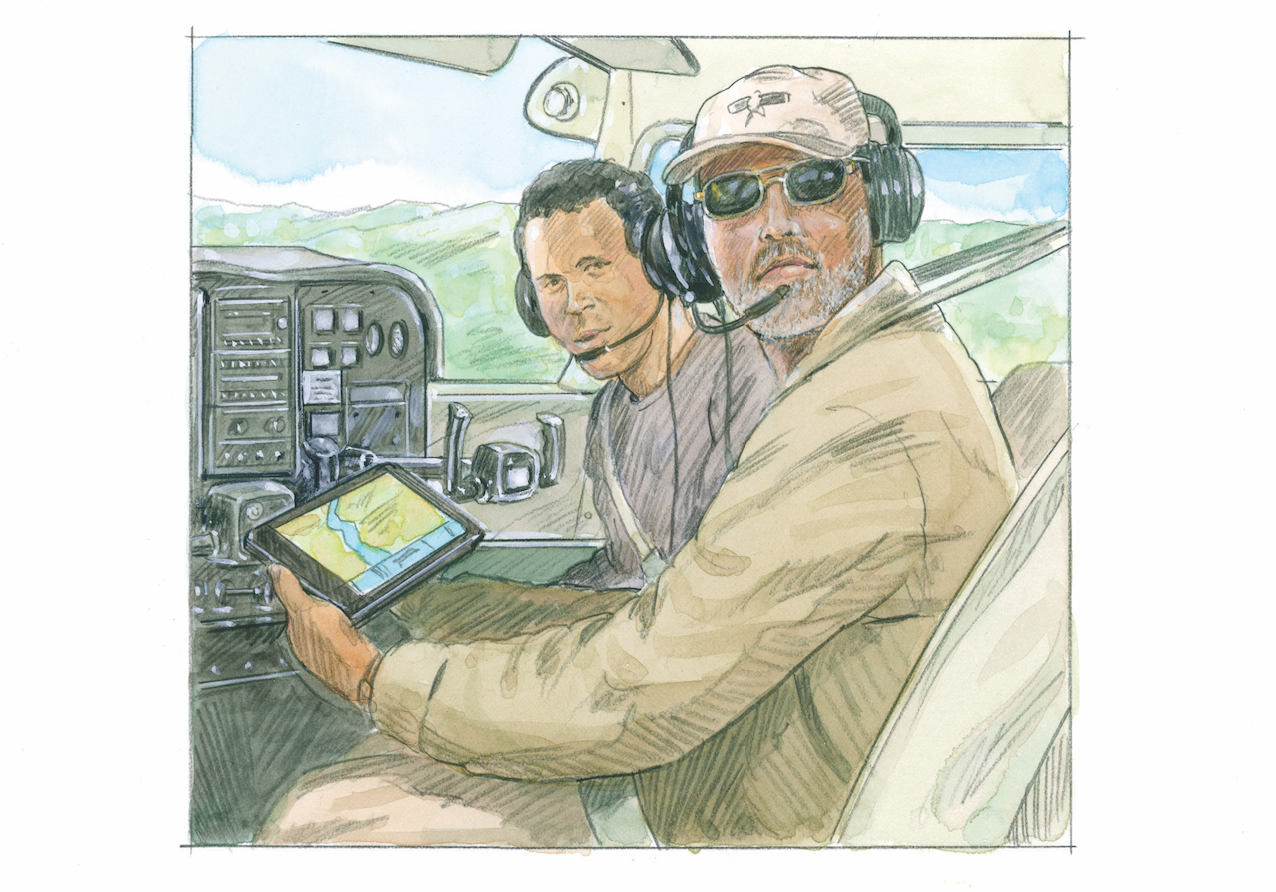

Now I'm feverishly thumbing through my iPad flight manuals looking for a chart---essentially a map of the U.S., segmented with scored sectors, each overlaid with different frequencies that allow the long arm of the doctor into our airplane.

I find the chart, dial in the right frequency and finally get the medical service on the radio; it's a four-way patch that includes our dispatcher in Dallas, the doctor in Pittsburgh, my attendants in the back and me up front. I listen in. My copilot begins his lunch.

Time from my initial contact about the situation to time the doctor is talking to his cabin assistants: 8 minutes.

Only it's not a doctor. I discover this after we've crossed more ground than I flew in all my initial flight training. The lead attendant has gone over all the particulars with the "doctor" only to be told that the doctor will now be brought into the conversation; everybody needs to stand down for several minutes while the doctor finishes his lunch. That last part is purely my own speculation, and I regret its inclusion here. Everything else has been true. The flight must now wait in our aluminum waiting room for our appointment. Pueblo, Colorado, slides by.

Apparently the nurse we've all been communicating with has the power to "prescribe" continued flight to the original destination under certain diagnoses---perhaps for presenters like "chilly," "frozen burritos" or "I ate at Chipotle."

Finally, after enough silence that I've wondered about my radio dialing ability again, Doctor grabs the microphone and quickly dissolves any notion that we will be landing anywhere other than Atlanta.

"The tingling in her fingers? That's because she's scared and not breathing deeply. The chest pain is likely something she's experienced the last couple days and is a reaction to the meds. Give her water, tell her to breathe deeply, calm down everybody and, for heaven's sake, please call with a real emergency next time."

I thought I heard him drop his fork. Maybe he didn't say that last part.

Order restores itself at 37,000 feet. The clouds part, the sun makes its way behind us, and my copilot asks, "Did I miss anything?"

Rob flies for fun and worked in another life. Flying now funds his wanderlust and inspires his creative urges.

Want to read more adventures and get insights from working pilots? Check out our AirFare archive.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest Plane & Pilot Magazine stories delivered directly to your inbox