Light-Sport Chronicles: Profiles In Vision: Ivo Boscarol

Routinely setting your goals way too high has its benefits

|

My knees wobble. That motion transfers to and magnifies the gyrations of the pole top I'm attempting to lift my left leg high enough to step onto. Climbing up the 33-foot wooden pole, lumberjack style, was challenge enough. Now, I'm wondering: What in the world was I thinking?

Welcome to Slovenia, and let's raise our glasses to setting your goals too high. Already smitten at Oshkosh by a flight in Pipistrel's Virus S-LSA cruising motorglider, I had come here to fly the company's other models at the factory that lives in the western part of former Yugoslovia. This greenest, most environmentally friendly building in Slovenia is solely powered by 11 different sources of renewable energy, from solar panels to geothermal heating.

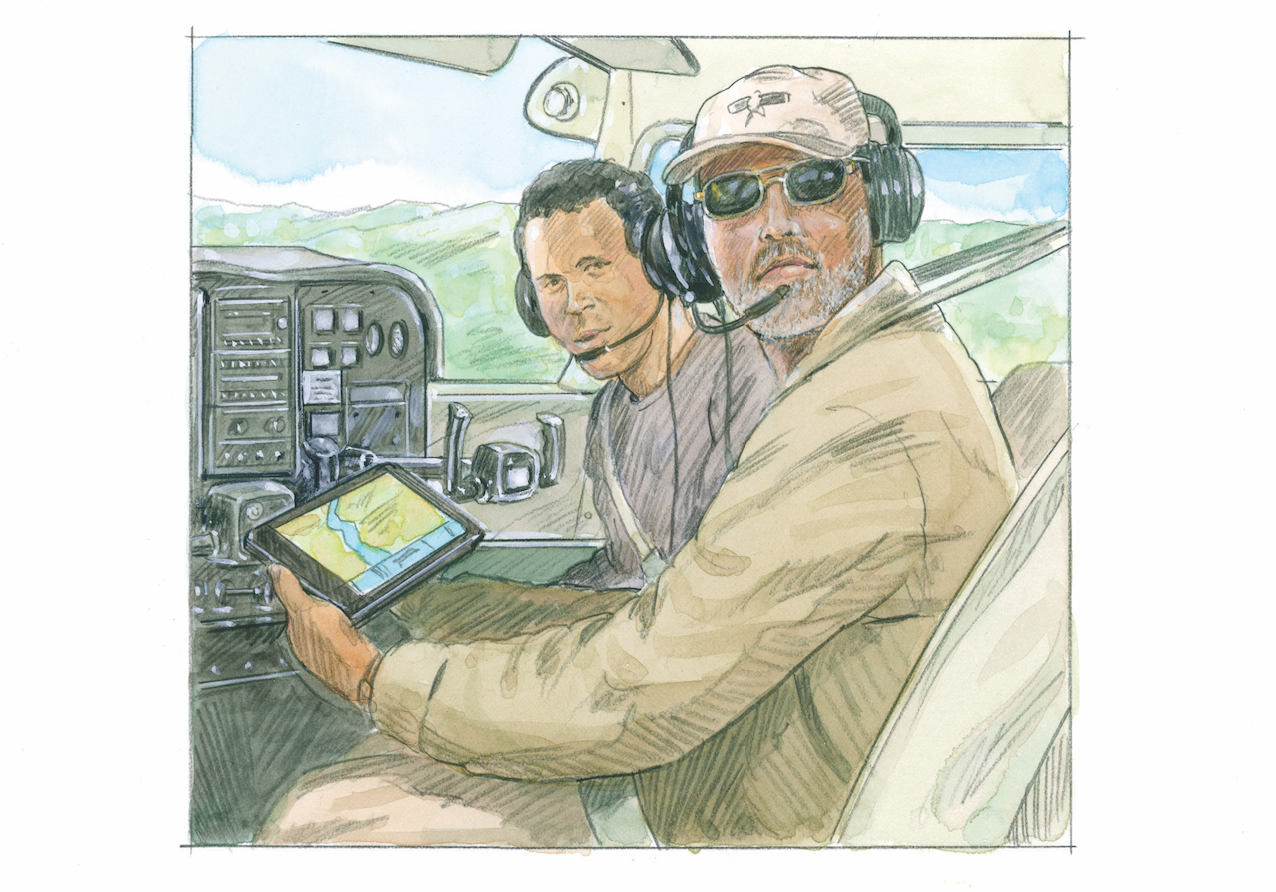

My agreeable companion for this busman's holiday was Rand Vollmer, the ever-cheery LSA dealer who heads up SALSA Aviation out of Texas. We met at Venice's Marco Polo Airport, and drove 90 minutes over the border to Ajdovšcina, Slovenia.

There was just one catch, and it goes by the name burja. The factory nestles in a deep, narrow valley between two high mountain ridges. That Venturi-like geology sets up truly nightmarish winds when it's blowing just right. The burja blew just right for our entire five days. All those lovely white Pipistrel airplanes never saw sunlight my entire visit. Boo-freakin'-hoo. Maybe the winds are why Pipistrel is building another factory in Italy to produce its upcoming (2013) Ferrari-like Panthera four-seat 200-knot cruiser. The Panthera will be powered by gasoline (including auto gas), hybrid gas/electric or pure electricity.

On to plan B...except there was no plan B. Undaunted, two days later, I sat across from Pipistrel's founder and head honcho, Ivo Boscarol. We chatted about his design team's stunning achievement in winning the NASA/Google CAFE Green Flight Challenge with the all-electric powered Taurus Electro G4. That stunning engineering milestone earned Pipistrel a cool $1.35 million, and overnight shifted everybody's expectations of viable electric flight from "medium-term" to "just around the corner."

Ivo Boscarol is a tall, dynamic yet wholly accessible guy, with the easy bonhomie of someone who knows what he's doing but doesn't wear it like a Rolex watch. Rand Vollmer says he's a "rock star" in his home country. He's a bit of a Renaissance maverick too, having done everything from professional photography to studying economics to running his own photo-printing business to managing the political campaign of the man who came in second to the current president of Slovenia.

A quarter century ago, he saw an Italian trike fly and said, "That's for me!" He smuggled one into then-Yugoslavia: Civilians couldn't legally fly small aircraft. "On one trip, I said it was a big bunch of tubes for a radio antenna. The next, it was canvas for a tent, then an engine for a motorboat. I assembled it here at the airfield, which was a military-only installation."

Boscarol flew the trike secretively between dusk and darkness. The name Pipistrel comes from the Italian pipistrellus, for bat, which is what the locals thought it looked like. Before long, he became known as the trike-upgrade go-to guy. Not long after that, he designed his own trike, and began producing them under the Pipistrel banner.

More than 1,000 aircraft later, with five models in full production and two more designs in the pipes, Ivo Boscarol is a man with a clear vision for his company. "My philosophy is simple: Set the goals too high, or you are dead.

"I have very good engineers, but the concept of all our aircraft and the strategy of how to run the company is mine," Boscarol continues. "I have to be enough of a visionary to see what's possible for us to sell. Normally, when I present a concept, the feedback from my development team is, 'What? That's not possible!' After one or two weeks, they say, 'We were thinking, maybe we can do this, or tweak that,' and finally they say, 'Yes: We can do it.'"

The winning G4 story is a perfect case study. "We decided," he says, doing his best to convey what he doesn't quite have the English for, "to build it the way your spouse does on Sunday when making the best possible lunch from what's in the refrigerator."

"Oh, you mean a kind of 'leftovers' airplane," I say.

"Something like this, yes," Boscarol says with a devilish smile. "It allowed us to meet the CAFE challenge parameters, be affordable and give us a good chance to win."

Boscarol's overarching philosophy has been to make Pipistrel a great place to work. "Profit and high salaries are not the most important point," he says in his deep, commanding voice. "We like to set our goals very, very high. And we like to be successful. Being successful is more important than money in this company. We have never taken one single Euro of profit out of Pipistrel. All the profits go into future development."

So, here I am near the top of that telephone pole a day later, with the entire staff on a company-funded team-building recreational weekend in eastern Slovenia, face-to-foot with my own too-high goal. The pole gyrates rhythmically, everybody's watching, I don't think I can do it, but I can't back down...Rand is making a video down below! I summon all my left leg has, and will myself to stand. To my surprise, the creaky old knee comes through and I'm standing on that nine-inch-diameter circle, hands out wide for balance, relieved and enjoying the cheers. I leap into space and my teammates safely belay me back to good old Slovenian dirt.

A trivial pole climb for a gimpy editor is nowhere near as profound as creating a successful, safe airplane out of an idea. But as Ivo Boscarol showed me, and is demonstrating to the world of light aircraft with each new design, this notion of setting your goal too high can end up feeling mighty good. Mighty good indeed.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest Plane & Pilot Magazine stories delivered directly to your inbox