Missing In Alaska

The remote and rugged terrain of Alaska hides the fates of hundreds of missing planes and people. Does new technology hold the key to making such mysteries a thing of the past?

With the recent introduction of a podcast, Missing In Alaska, about the 1972 disappearance of a Cessna 310 twin-engine light plane carrying United States Representatives Hale Boggs (D, LA) and Nick Begich (D, AK), along with an aide and the pilot, the still-unsolved case is once again very much in the news.

Alaskans have not forgotten about the disappearance of the small twin-engine plane, or the massive, ultimately unfruitful search that followed--there has never been a shred of debris recovered from the presumed crash. But at the same time, they are not dismayed by it. Sadly, such tragedy is part of the fabric of life in the 49th state, a state that relies on small planes for much of its commerce and transportation. Such crashes continue to this day.

On September 9, 2013, Alan Foster landed in the southeast village of Yakutat on the final leg of an almost 4,000-mile-long journey that began when he picked up his recently purchased PA-32-360 in Atlanta. Foster had over 9,000 hours of flight time and had flown for a variety of Alaskan air taxis and commuters. He was only 360 miles from home in Anchorage and eager to return to his family. After refueling, he departed and contacted Juneau flight service for an update on the weather, explaining he would stop in the town of Cordova, about 200 miles away, if conditions required. Eighteen minutes later, between the Gulf of Alaska and Malaspina Glacier, radar showed a transponder target near 1,100 feet. If it was N3705W, this was the last record of the aircraft before it, and Foster, disappeared.

Because of Alaska's size, its rugged terrain and its often severe weather, flying there is a serious endeavor unforgiving of mistakes. The state covers 663,000 square miles of land and has a coastline 6,640 miles long. It contains North America's tallest mountain, active volcanos, two national forests, over 100,000 glaciers and the mighty Yukon River. Moreover, its weather, with fast-forming storms, hazardous icing conditions, and frequently obscured mountains and passes, results in a widely varied climate that is often not conducive to flight by visual references. Given all of these factors, disappearances in this overwhelming landscape are part and parcel of the state's reality and, even more so, its ever-powerful mythology.

Occasionally, Alaska does give up its secrets and missing aircraft are eventually discovered. In 1979, two hikers at the head of the Ivishak River, in what is now the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, stumbled upon the totally destroyed wreckage of a Grumman Goose that had impacted the mountainside at the 5,700-foot level. The subsequent investigation determined that it was the remains of N270, which disappeared on August 20, 1958. Flown by Clarence Rhode, the Alaska regional director of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the flight also included his son and a fellow Fish and Wildlife agent. They were last seen by field scientists at Peters Lake, and their intended destination was a supplies cache for Fish and Wildlife at Porcupine Lake. Their crash site was 25 miles from their destination, but because of the vegetation, it was never seen during the initial search.

The crash of Rhode's Grumman was hardly the first, or last, case of an aircraft disappearing in a remote part of Alaska. Aircraft have gone missing in the 49th state since long before it was a state. In 1925, Noel Wien's fate was unknown for several days after he was blown off course by strong winds over the Sawtooth Mountains when returning to Fairbanks from the village of Wiseman. As later recounted in The Flying North, he ran out of gas and oil in his Standard biplane and was forced to land in the dark on a sandbar.

On his hike out, he forded three rivers (one frozen, two requiring him to build small rafts), shot rabbits for food and expended an enormous amount of effort stumbling across the slushy muskeg. Wien's logbook entry later offered only the shortest of records from this adventure: "Forced down, gas and oil out, walked 40 miles back."

The episode was, for all its inherent drama, just another day on the job for Wien but also indicative of the harsh reality for territorial pilots. Headlines announcing searches for lost and overdue aircraft were common in newspapers from the 1920s and '30s, when pilots flew to some of the most remote regions looking for missing aviators. Two of the most high-profile searches took place in 1929, first for Russ Merrill, whose Travel Air floatplane was never found and is believed lost in Cook Inlet, and later for Carl "Ben" Eielson, whose body, along with mechanic Earl Borland's, was located in the wreckage of his Hamilton Metalplane in Siberia three months after it disappeared while flying a fur contract.

During World War II, the U.S. Army Air Forces maintained files on the many crashed and missing military aircraft in Alaska, most of them associated with the Lend-Lease program. After the war, all search and rescue operations in the territory formalized and were handed off to the military. Several different squadrons and air wings over the years were placed in charge, under the auspices of the U.S. Air Force's Alaskan Air Command, until 1994 when the the Alaska Air National Guard's Alaska Rescue Coordination Center became the primary respondent for overdue inland aircraft. (The Coast Guard remains the primary respondent offshore.) The system continues to include civilian pilots and groups, however, a necessity due to the state's uniquely challenging topography.

But while search and rescue operations have been fairly consistent for decades, record keeping has not. To learn about much older flights, such as Russ Merrill's in 1929, researchers must visit archives and libraries to pour over historical records, and they often walk away disappointed. For those civilian aircraft lost since 1962, however, the situation is far better. The Alaska regional office of the NTSB in Anchorage has curated missing aircraft files since 1962. It is in this nondescript federal building where everything that is known to date about Alan Foster's final flight, and about 40 others like it also still missing, can be found. The reports range from those with scant details about aircraft, pilot and last location to far more in-depth reports, which include witness statements and specific search references.

By far the most famous missing aircraft in state history is the Cessna 310 operated by Pan Alaska Airways, N1812H, which disappeared on October 16, 1972, between Anchorage and Juneau. In addition to pilot Don Jonz (who was chief pilot of Pan Alaska), the flight included Alaska Congressman Nick Begich, aide Russell Brown and Louisiana Congressman Hale Boggs, the House majority leader. The men were planning to attend a rally for Begich in Juneau when the plane went down somewhere during the three-and-a-half-hour-long flight.

Jonz filed a VFR flight plan upon departure from Anchorage at 9:00 a.m. stating his intended route was via the V-317 airway to the village of Yakutat, and then direct to Juneau. Traditionally, pilots operating VFR along V-317 fly southeast over the Turnagain Arm of Cook Inlet, through Portage Pass, over Prince William Sound to Johnstone Point, and then on to Yakutat. Weather in this entire area was marginal and not recommended for VFR on October 16 and included a ceiling of 700 feet overcast in Yakutat with visibility of 1½ miles and fog, and indefinite ceiling in Juneau, 500 feet obscured, half-mile visibility in fog. Portage Pass was forecast to be closed, and moderate rime icing was forecasted en route.

Dozens of civilian and military aircraft (as well as the Coast Guard, Merchant Marine and fishing vessels) looked for the wreckage in one of the largest aerial searches in U.S. history. Covering 325,755 square miles and including over 1,000 sorties and 3,600 flight hours, the search encompassed a large swath of the Prince William Sound and Gulf of Alaska coastlines, some of the state's largest glaciers and even the towering Wrangell St. Elias Range. Additionally, Portage Pass was searched twice by ground units. Unfortunately, N1812H did not have an Emergency Locator Transmitter (ELT), as required by a recently passed Alaska state law. On November 24, the search was terminated, and on December 29 the four men were declared dead.

In short order, the 60-some pages of weather reports, witness interviews, and pilot and aircraft history concerning N1812H were relegated to the same file cabinet in the same back room in Anchorage where they now reside with the records for N3789L, a C-172 lost between Northway and Juneau in 1967; N8022Z, a C-206 lost between Anchorage and King Salmon in 1986; N56877, a Piper Cherokee lost near Chitina in 1999; and N9313Z, a de Havilland Beaver lost in Katmai National Park in 2012. Along with all of the missing aircraft files, these cases wait for a new discovery or development that will prompt a final closure to their long open investigations. And while stubborn conspiracy theories in some quarters have surrounded the Begich/Boggs crash for decades, Alaskans view it as another tragic but all too familiar entry in the state's aviation history. Aside from its famous occupants, the crash of N1812H is little different from thousands of others that preceded it.

This fact is particularly clear to Clint Johnson, Alaska region chief of the NTSB, who explains, "The missing Pan Alaska Airways Cessna 310's anticipated route would have taken them over areas of remote inland fjords, coastal waterways and steep mountainous, glacial-covered terrain. The area between Anchorage and Juneau is enormous, so it's anybody guess where the airplane ended up. To complicate matters, icing conditions were forecast, and the airplane was not equipped with any type of deicing equipment, all of which are common factors in aviation accidents here in Alaska."

Johnson has not given up on N1812H being found, however. "Every few years or so, someone will find some aircraft wreckage within the search area, and we always hope that it might be from the missing Hale Boggs/Nick Begich flight, but so far, we've had no luck. Frankly, there are several airplanes still missing in that area, so we take any wreckage discovery seriously."

One positive aspect of the disappearance of N1812H is that it spurred Congress to act, and a law was passed in 1973 requiring all U.S. registered civil aircraft be equipped with ELTs. The widespread use of ELTs had a powerful impact on search and rescue operations, but in the decades since the equipment was mandated, technology has seen tremendous advances that go far beyond its capabilities. This was clear in a recent accident that has resulted in a personal legislative effort that one Alaskan family would like to see for aviation safety.

On April 14, 2015, at 1:15 p.m., pilot Dale Carlson contacted Anchorage Approach to report engine trouble while flying his Cessna 180 over Prince William Sound. Carlson was about 60 miles from Valdez and had been cleared for an instrument approach when he developed engine problems while descending from 10,000 to 8,000 feet. Six minutes later, Carlson declared an emergency and reported he would attempt to land on the beach of a nearby island. The controller acknowledged his predicament and then, two minutes later, received a final, brief, transmission from the aircraft. An ELT signal was detected at 1:30 p.m., and a search immediately commenced.

Based on the last radar contact, the Coast Guard initially focused its search on the east side of Perry Island. However, when Carlson's family was contacted, they immediately made searchers aware that N9247C carried Spidertracks, a satellite tracking system for aircraft, and based on the information they had through it, Perry Island was not where Carlson's plane would be found.

"It took me a few minutes to explain what exactly Spidertracks was telling us about my dad's flight," explains John Carlson. "But when I made it clear to them that we had the last altitude, the airspeed, the heading, everything, they understood that they could take that data and see exactly where he was going. We gave the entire last flight to them, and they were able to triangulate where the plane should be."

About 2:40 p.m., searchers changed their focus to the east side of Culross Island, seven miles from Perry Island. At 5:00 p.m., Dale Carlson's body was found on the eastern shoreline there, along with the left landing gear and strut from what is believed to be his aircraft. The rest of the Cessna 180 was likely sunk in Prince William Sound.

Based on what happened to his father, Carlson is certain that improved technology would have an overwhelmingly positive impact on the aviation community. "I am very grateful to the people who looked for and ultimately located my father," he says, "but had we not had the data available to share with them, I do not believe he would have been found."

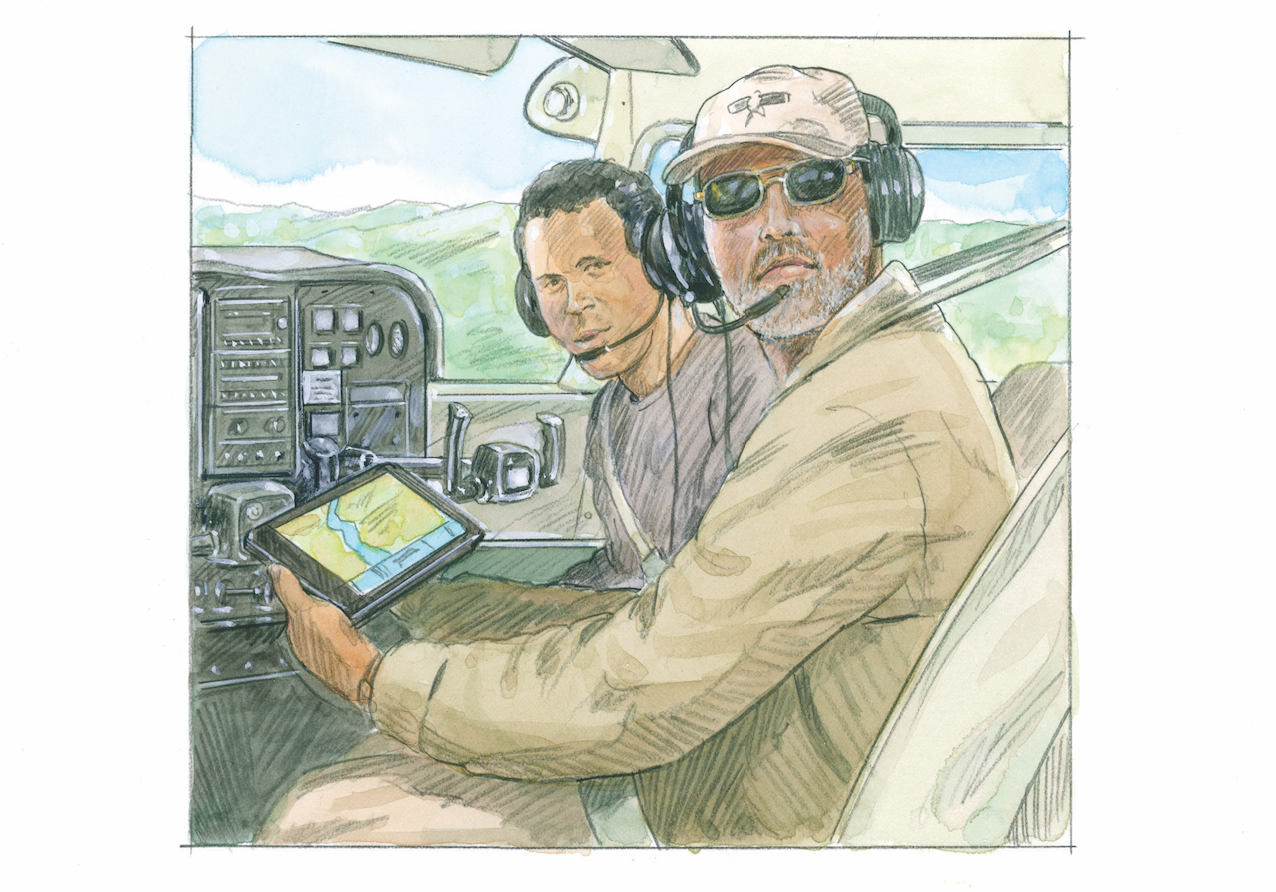

Other new technologies also hold great promise. The FAA's mandated ADS-B interdependent aircraft tracking system allows controllers to keep track of aircraft in many locations, but there are still sizable gaps. Personal locator beacons, some of which can automatically alert authorities to the whereabouts of a downed flight, can summon help to the exact location of the accident. And personal messaging devices allow pilots to call for help via satellite-linked text messages.

For all the potential solutions to future accidents that modern technology offers, the quest for answers to the past remains. There are still families longing for the day when Alaska's shifting landscape reveals the fate of their loved ones. And collectively, all of these losses stretching back more than 80 years weigh heavily on the state's residents.

"We will continue to hope for resolutions to these accidents," says the NTSB's Johnson, "no matter how long it takes. We will wait for the moment when we finally are able to say we know what happened."

To date, there is no further information on the location of N3705W or what became of its pilot, Alan Foster. The file remains open.

Colleen Mondor is a writer and historian who has been covering Alaska aviation for decades. She is the author of "The Map of My Dead Pilots: The Dangerous Game of Flying in Alaska" and is currently at work on a book about the 1932 Mt. McKinley Cosmic Ray Expedition.

For more about technologies used to improve remote operations, check out our article on How To Keep From Going Missing!Forever.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest Plane & Pilot Magazine stories delivered directly to your inbox