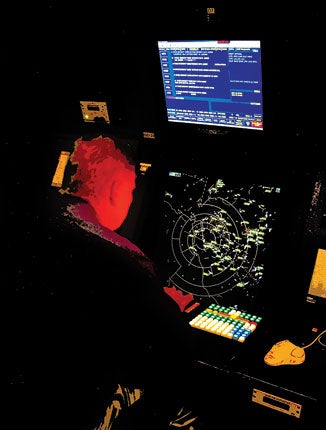

Under NextGen, air traffic controllers see a combination of ADS-B and radar data, with automatic validation to prevent "spoofing." |

I apologize for the title; I couldn't resist. It was inspired by a presentation with the provocative title, [The] "Ghost Is In the Air (Traffic)," written by two French researchers and presented last year at Black Hat, an annual conference on computer and network security. The presentation did a good, if incomplete, job of explaining how ADS-B works, and went on to posit that by using simple equipment, it would be possible to "spoof" the system---by recording legitimate signals sent from ADS-B-equipped aircraft and playing them back to fill ATC scopes with false targets and force airline pilots into radical deviations around threats that would turn out to be bogus. The story was picked up and reported by many outlets in the general press, and Plane & Pilot heard from readers who were genuinely concerned.

After speaking with people in a position to know how the system works, now I can confirm that ADS-B won't make U.S. airspace less secure---far from it. It will enhance the safety and security of all operators (especially those who file and fly IFR). However, it turns out that one problem identified by our French friends is real and will have an impact on some users---in a nutshell, with ADS-B, airspace becomes safer and more secure!but less private. To understand why, we'll need to review how air traffic was managed before ADS-B and how the new system (part of the FAA's Next Generation initiative) changes things.

Operations in most U.S.-controlled airspace requires a transponder, which responds to interrogation from primary and secondary surveillance radar signals, sending altitude and a four-digit "squawk code" to the radar site. Air traffic controllers use that to identify where aircraft are located, keep them separated if operating on IFR flight plans and offer traffic advisories if they're operating VFR. That system has been in use since World War II and works well, but it has problems. Radar isn't all that accurate at long ranges, and aircraft positions are only updated when an aircraft passes through the radar beam (typically every 12 seconds). As a result, ATC requires a five-mile separation between each aircraft. And there are some locations with heavy air traffic---including large parts of Alaska and the Gulf of Mexico---where radar isn't available.

ADS-B, part of the Next Generation air traffic system (NextGen), is autonomous, sending the aircraft position, a unique 24-bit identifier, N-number (or airline flight number), altitude, transponder squawk, heading, velocity and other data every two seconds. It's dependent on GPS (or an equally accurate system) for its position information. The data transmitted by ADS-B is used by ATC for surveillance of traffic in their airspace, broadcast using one of two radio links through a network of ground stations being installed by ITT Corporation under contract to the FAA. ADS-B also differs from radar-based surveillance in being a two-way system; in addition to broadcasting aircraft position to ATC (and other aircraft), if you have the right equipment, you can receive information including the position of nearby aircraft and, in some cases, free weather information.

Now that we've got that out of the way, let's review the scenario presented at the Black Hat conference: A hacker buys an ADS-B receiver, connects it to a data recorder and records the broadcast information for one or more real airplanes. Then he connects that recorder to a transmitter and plays the broadcast information back---repeating it endlessly. Pilots and air traffic controllers in the area see an endless stream of "ghost" airplanes requiring deviations. Pushed to its limits, this would result in a "denial of service" situation, with ATC unable to provide IFR separation service to pilots.

ADS-B does raise privacy issues. The Planefinder website collects worldwide data from enthusiasts with ADS-B receivers and displays aircraft positions in real time. |

It sounded impressive, and the general press picked up on it---not helped by an FAA response that described ADS-B security issues as too sensitive for public discussion. But, after talking to experts in a position to know how the system really works, I can tell you that any attempt to inject "ghost" aircraft into the U.S. air traffic control system will be a lot more difficult than what was described at Black Hat.

Why? Because you have to consider the air traffic control system as a whole, not just a single aircraft or ground station. The airline pilot in that scenario is flying on an IFR flight plan in controlled airspace. He's being monitored by an air traffic controller. In most U.S. airspace, he'll be seen on primary or secondary surveillance radar---and as we reported back in 2010 (and confirmed for this story by an FAA spokesperson), those radars aren't going away---all primary surveillance radars and half of today's secondary surveillance radars are being retained (some of which are paid for by the U.S. Air Force and the U.S. Department of Homeland Security). The presumed horde of ghost airplanes appear only on ADS-B, not on radar. ATC immediately knows they're bogus (this happens automatically, in a fraction of a second) and doesn't issue instructions to the pilot to deviate around them.

What if it happens in non-radar airspace? At all but the lowest altitudes, airplanes are covered by more than one ADS-B ground station. If only one station receives the signal, it's bogus. Depending on the particular kind of data link used, even a single station may be able to determine whether the ghost is real, based on signal timing. Finally, ATC computers will be looking to determine whether targets are moving appropriately. Does this mean the system is completely secure? Certainly not---but it's a lot more difficult to hack than what was alleged at Black Hat!

In fact, ADS-B makes it safer and more secure to fly---because for the first time, it provides a completely redundant backup to the existing radar-based infrastructure. Today, radar outages can and do lead to long delays and, if unmonitored, can create safety issues. And while it's rare, radar is vulnerable to jamming and spoofing. With ADS-B and radar complementing each other, the system as a whole becomes safer and more secure.

That said, there's one element in the "Ghost Is In The Air (Traffic)" presentation that's quite legitimate. It involves privacy rather than security.

Every civilian ADS-B transmitter has a unique 24-bit address. If you know that address, you can relate it to the airplane's N-number, and since ADS-B transmissions aren't encrypted, in principle, you can track any civilian airplane---at least while operating IFR (one class of ADS-B equipment intended for use mainly in piston airplanes offers a VFR-only "anonymous" function equivalent to squawking 1200 that generates a random 24-bit address and doesn't reveal your N-number).

If, like me, you've taken advantage of websites like www.flightaware.com to track your friends (and had passengers track you), that may not seem like much of a concern, but some operators of business-class aircraft aren't thrilled by it. There are legitimate concerns about the implications of accurate, real-time locations of every aircraft, searchable by N-number available on a website.

| FOR MORE INFORMATION |

| Ghost Is In The Air (Traffic) Presentation from Black Hat conference http://media.blackhat.com/bh-us-12/Briefings/ Costin/BH_US_12_Costin_Ghosts_In_Air_Slides.pdf |

| FAA ADS-B Safety Briefing www.faa.gov/nextgen/implementation/programs /adsb/broadcastservices/view/media/ MayJun2010-ADS-B.pdf |

| National Airspace System Capital Investment Plan FY 2013--2017 (FAA) www.faa.gov/air_traffic/publications/ cip/files/FY13-17/FY13-17_CIP _Complete_March_2012.pdf |

| Plane Finder http://planefinder.net/about/ ads-b-how-planefinder-works |

For better or worse, such websites exist (see the link to www.planefinder.net in the sidebar). Until now, the FAA was the only source for aircraft position data, and it dealt with privacy concerns by maintaining an embargo list of N-numbers whose positions weren't reported in the radar-based data streams on which sites like Flightaware are based. Sites like Planefinder, by contrast, depend on ADS-B data passed on by hobbyists who use ADS-B receivers to track airplanes. No embargo list applies in those cases---and the position data they report also isn't subject to the delays mandated by the FAA (and enforced by ITT, the U.S. ADS-B contractor).

In the "Ghost Is In The Air (Traffic)" presentation, this situation was exaggerated for effect: The presenters showed Air Force One being tracked. They went on to note that as a military aircraft, it might be able to use ADS-B modes that aren't available to the flying public. Sources in a position to know tell us that's quite correct---it's naive to assume that Air Force One will consistently report the same 24-bit address.

There are proposals to offer a similar capability to business aviation operators who have legitimate concerns about privacy: Instead of a single, hard-coded address that maps neatly to an N-number, an operator might be assigned a number of different addresses (if you're old enough to remember the movie Goldfinger, think of James Bond's Aston-Martin with the rotating license plates "valid in all countries.") But since ADS-B isn't just an American but rather an international standard, implementing such a proposal would require international negotiations. As one source told me, "Let's face it---if you fly in controlled airspace, you can't expect to do it anonymously."

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest Plane & Pilot Magazine stories delivered directly to your inbox