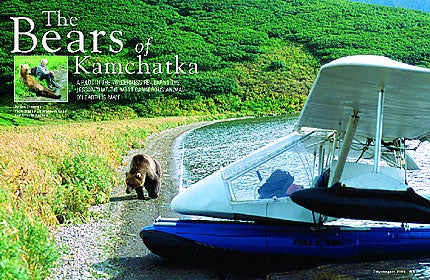

The Bears Of Kamchatka

A pilot in the wilderness re-learns the lesson that the most dangerous animal on earth is man

For Charlie Russell and Maureen Enns, it had been a mostly sleepless night. Straight winds of more than 100 miles an hour were not uncommon in remote southeast Russia, and the storms that came with them could last for days. Their tiny homebuilt cabin perched on the tundra was barely a refuge from gusts of air that found their way through the tiny imperfections in the walls, the roof and even the floor, bringing with them deposits of snow, dust or rain. At first light, their worst fears were confirmed: The wind had put their airplane on its back.

For Charlie Russell and Maureen Enns, it had been a mostly sleepless night. Straight winds of more than 100 miles an hour were not uncommon in remote southeast Russia, and the storms that came with them could last for days. Their tiny homebuilt cabin perched on the tundra was barely a refuge from gusts of air that found their way through the tiny imperfections in the walls, the roof and even the floor, bringing with them deposits of snow, dust or rain. At first light, their worst fears were confirmed: The wind had put their airplane on its back.

Russell and Enns had come to Russia's Kamchatka Peninsula for the first time in the spring of 1994 as emissaries of the Great Bear Foundation, an American group interested in a firsthand report on the degree of brown-bear poaching in the area. Kamchatka was an area the size of California, but almost empty of people, and although much of it was officially a "sanctuary," harvesting the prolific wildlife could be a lucrative livelihood for those who are willing to risk a chance encounter with the "lone ranger" who hiked there. Bear parts, especially gallbladders, brought almost unimaginable amounts of money in third-world markets.

At the time, Russell had no way of knowing that this wilderness area would ultimately become the confluence of his two great passions---flying (he's been building and flying his own aircraft for more than 30 years) and bears. Raised by a father who was a wilderness outfitter and hunter in Southwest Alberta, Canada, Russell spent some time as a hunting guide himself. But the older he got, the myths he had always been taught, that bears were unpredictable and inherently dangerous, didn't match his own experiences with them. His partner, Enns, came by her interest in bears as an artist, brought into focus after traveling Banff National Park, in Alberta, on horseback. Now, sitting around a campfire with their Russian guide, Igor Rebenko, they poked at the coals and talked. Finally, Russell and Enns felt comfortable enough to share with Rebenko a rather unconventional thinking about bears.

There was a mindset in the world that bears and human beings were natural enemies. There was one year in Canada when the high-country berry crop failed, forcing the bears into the valley floors to escape starvation. Thirteen hundred of them were killed by wildlife officials and the public before their hibernation stopped the carnage. Even in national parks---areas set aside to ensure the survival of wildlife---bears that get too comfortable with their human visitors are either relocated or exterminated. With the world's wilderness rapidly disappearing, the species' ultimate survival might depend on the cooperation of bears and humankind to cohabitate.

The next spring, Rebenko had already laid the groundwork for the couple's experiment. It was in a remote site on the Kamchatka Peninsula, home to more brown bears than the rest of the world's populations combined. Russell's aircraft, a single-engine Kolb, left Seattle on a ship bound for the Russian seaport of Petropavlovsk, epicenter of the Russian nuclear submarine presence during the Cold War and equally infamous as the city where a Korean airliner was shot down in 1983. At the time, Russia was in the first throes of chaos from the collapse of the Soviet Union, and getting permission for an American to fly a lightplane would, in no way, be a certainty.

"There was really no category of aircraft in Russia that the Kolb fit into, and it sort of fell between the cracks," remembers Russell. "We got permission from one department and not another. Igor did most of the negotiating, editing facts over here and telling the truth over there."

Even after the partial blessing from authorities, Rebenko gave Russell a list of areas from which he needed to stay away. On top of that, Russell was not allowed to use a radio.

"We couldn't put any English-speaking voice out over the airwaves. So it meant living and flying in the backcountry without support, which was pretty hairy," shrugs Russell.

Enns left Petropavlovsk in late June in a chartered Soviet Mi-8 helicopter stuffed with provisions for the summer, while Russell tagged along in the Kolb. With a storm approaching from over the mountains, they pitched a tent on the spot where they would ultimately build their cabin on the banks of Kambalnoye Lake, home for their research for the next seven years, until a heart-stopping day in the spring of 2003.

At times, each of them entertained thoughts that the whole idea of dragging themselves and an airplane thousands of miles to the middle of nowhere to live with bears was sheer folly. Russell was forced to start from zero to acquire local flying knowledge, but the float-equipped Kolb turned out to be the perfect companion.

"I could land on water or I could land on the tundra if it was damp," discovered Russell. "Sometimes, I got trapped if it was too dry and I'd have to wait until the morning dew until I could take off again." In addition to the winds and rain that could arrive with devastating unpredictability, the lake could also be sealed into the mountain valley by a deep fog.

"One day, when I was trying to get back to our cabin, I spotted this hole in the fog. I put out some flaps and began circling to get down," smiles Russell. Then the Kolb stalled and entered a spin. "I realized I had spun it and was turning, but I had to let it spin to where I knew I'd be facing away from the rocks. I had to really control my panic to make sure I didn't pull it out at the wrong moment."

That "hole" that Russell had found formed fairly regularly and, over the years, became an important corridor from which Russell can come and go from the lake on foggy days. He did, however, drop the spin from his daily techniques.

|

| And like all children, the cubs needed to learn discipline. They were taught the word "no," and from the beginning, there was no grabbing allowed. |

On a clear day, Russell often would count more than 100 bears during a single flight. He watched females lead as many as four cubs down trails worn exclusively by brown-bear paws. He watched bears play in the ocean waves and saw them splash in a sea of salmon. But to his and Enns' great disappointment, nearly every bear they tried to approach in the Kamchatka wilderness ran away from them. Years of poaching in the area had taught the bruins that contact with human beings could be lethal. Or were Russell and Enns just plain wrong in believing that bears and people were not natural enemies? They left Russia at the end of their first year, faced with the real prospect that their project was meaningless. Until Rebenko brought them some exciting news.

Three orphaned female brown-bear cubs had ended up in a zoo outside of Petropavlovsk. Although the official Russian position did not favor releasing the bears to Russell and Enns, the zookeeper's position did. He helped load the three 15-pound bears into a box for transport, and with a fair amount of squalling from the cubs, the zoo's first cub-napping was in progress.

Raising the cubs, named Chico, Biscuit and Rosie, in the wilderness was, in many ways, no different from bringing up human kids. They wanted to eat and they wanted to play. Russell and Enns would take them on walks along Kambalnoye Lake, and the cubs' noses would lead them everywhere. The cubs developed a sweet tooth for the flowers that began to bloom on the tundra, and the cream-colored rhododendrons near the cabin didn't stand a chance. Eventually, Russell and Enns taught them to fish by placing a salmon carcass under several inches of water. The bears then figured out how to stick their heads into the river and retrieve a delicious snack. Later, Russell would herd live fish into the shallows, and Chico, Biscuit and Rosie learned to pounce on them.

The cubs had dug a small den under the cabin and were hiding there when the storm that flipped Charlie's airplane blew in. Three days later, when the winds finally calmed down, they watched as Russell and Enns looked over the damage. Some spare aluminum tubing was used to repair the stabilizers, the rudder from a kayak reinforced a damaged spar, and a small skillet was heated to heat-shrink some extra Dacron cloth over the holes in the Kolb's fabric. Repair of the aircraft was critical---it was a 25-mile hike to the nearest human beings---but not so important as to interrupt the rearing of the cubs.

And like all children, the cubs needed to learn discipline. They were taught the word "no," and from the beginning, there was no grabbing allowed. It would be no time before the bears' natural strength could overpower their human parents. Although Russell would sometimes arm wrestle and play with the cubs, they were forbidden to repeat the same shenanigans with Enns. But Chico loved to joke around, so she would bring her teeth within inches of the tempting rolled-down flaps of Maureen's waders, then back off again at the sound of her "no."

Other bears---wild bears---also began to accept Russell's and Enns' presence. "One female named Brandy looked over the situation and decided that we were trustworthy enough to babysit her cubs, Gin and Tonic," remembers Russell. "She would wander along the lake shore, and when they were a little distracted, she would disappear. The first time she did it, they were very upset, but later on, when she did that, they didn't mind at all. They would play around us, close enough that they'd bump into us. It was the most gorgeous situation."

By the first of October, each of the 15-pound cubs weighed more than 150 pounds, and their coats had become luxuriously thick. The snow line began working its way down the mountainsides toward the valley, and the bears spent more and more time in a deep drowse. Winter was coming to Kamchatka, and instinct was telling the cubs that it was time to den up. Russell and Enns would return to Canada, not knowing anything more of their cubs' destinies until the spring. But they left with something very valuable, living proof that bears and men don't always have to be enemies.

The experiment continued over the next two years. Each spring, Russell and Enns would return to Kamchatka, and each spring, the bears were there to greet them. As word of their success spread around the world, funding for their project became easier. Soon, the cabin at Kambalnoye Lake was equipped with a satellite uplink, and regular reports of the bears' progress, sometimes even with digital photographs, were zipped out of Russia to the waiting world. The couple also began raising money to fund a year-round effort to protect animals against poaching. "It was not fair to teach bears that people were nonthreatening if it meant that they could be killed because of their trust," states Russell. Cabins were built to place rangers at key positions in the wilderness, and the Kolb was used to watch the progress of the project and ensure that the money that they had raised was ending up being used as it was intended.

"People asked me when I was going to get a real plane," grins Russell. "The answer is easy: when a real plane is developed that can do what this plane can do. To me, these types of aircraft are never taken seriously as a helpful tool. This was my business aircraft."

But in 1999, the couple returned to the cabin in Kamchatka to find only Chico and Biscuit---with no Rosie by their side. The three sisters were practically inseparable, so the fact that Rosie was missing was ominous. On a bench beside a small lake, a place where the three cubs had regularly played, but now avoided, Enns found the remains of the missing cub, the victim of a predator male bear.

| Kamchatka Bears Resources | |

| To obtain a copy of Grizzly Heart by Charlie Russell and Maureen Enns, go to www.amazon.ca. | |

| To order the DVD on the PBS "Nature" program, "Walking With Giants," featuring Charlie Russell, Maureen Enns and their bears, go to www.pbs.org. | |

| To contact Charlie Russell and Maureen Enns, visit their Website, www.cloudline.org. | |

For Russell and Enns, it was a reminder that their project in Kamchatka would not go on forever. Raising cubs or children is, at best, bittersweet because no one knows what the future really holds. By the end of August of that year, Chico wandered away, perhaps over the mountains toward the Sea of Okhotsk where migrating bears enjoyed the final days of salmon runs. When Russell and Enns left that fall, only Biscuit remained. Rosie was gone, and there was no way to know if they would ever see Chico again.

Over the next few years, however, the project continued. Brandy, the bear who had entrusted them with babysitting, began leaving her new cubs, Lemon and Lime, for Russell and Enns to watch over. And Biscuit had a wonderful surprise for them: Sometime, come spring, Russell and Enns would become proud grandparents of baby cubs.

The spring of 2003 arrived and so did Russell and Enns, who were excited to see Biscuit's offsprings. The lake was still frozen and the snow had drifted deep around the cabin. "I wanted to see Biscuit come out of her den with her new cubs, but it didn't happen that way," recalls Russell.

Instead, there wasn't a bear in sight. Last fall, after Russell and Enns left, poachers had used their cabin to kill the bears around Kambalnoye Lake. More than 40, including Biscuit and Brandy, were gone. A single gallbladder was left, nailed to the cabin wall.

"It was incredibly devastating." Russell pauses before continuing. "It was an awful way to end our project." Russell and Enns are still tormented by the thought that their work of acclimating the bears to humans might have enabled the poachers to easily walk right up to the bears and kill them.

Today, the couple is still grieving for their loss. But in December of last year, the poachers who were responsible for the genocide at Kambalnoye Lake were arrested, giving Russell and Enns some sort of closure to the tragic event.

In the past few months, Russell and Enns have turned this tragedy into a positive as they try to educate and fight for conserving the Kamchatka brown-bear population. Next spring, Russell plans to fly his Kolb in Russia again, his attention now focused on the Kamchatka Bear Fund, a nonprofit program devoted to the long-term conservation of the Kamchatka brown bears, and the ranger program that he and Maureen initiated is still ongoing. Word is spreading about their devotion to the bears. Wildlife conservation groups worldwide, including the United Nations---which designated the area as a World Heritage Site---have focused on the 33 species of mammals and 145 species of birds that make Kamchatka one of the world's final and most remarkable wilderness areas. Russell has even written a book, Grizzly Heart---which has now been translated into six languages---in which he lovingly talks about the story of the bears of Kamchatka. In fact, work has already begun on a major motion picture to bring the book to the screen. And Russell, who once found himself sharing his thinking about bear and human relationships to a relatively few, now speaks before standing-room-only crowds. Ironically, perhaps, the cubs' sacrifice has started a worldwide examination of how bears and human beings can coexist, a conversation that otherwise might not have happened at all.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest Plane & Pilot Magazine stories delivered directly to your inbox