When Training Turns Lethal

The safest kind of flying, statistically at least, has its own hazards. Here’s how to wrap your head around the risk and keep your sunny side up.

When it comes to high-risk flight, we usually think VFR into IMC, low-level maneuvering or run-ins with thunderstorms. Rightly so, too. Those scenarios, along with the ever-present villain "loss of control" lurking nearby, are the riskiest in flying. Training, on the other hand, is, statistically speaking, the safest aviating you can do this side of hangar flying.

But don't let that fool you into thinking that it's risk free. It's not. Instructors need to know when the limits of safe flight are being approached during training and when to step in to keep safety from being compromised. At the opposite extreme, avoiding all abnormal parameters, merely lecturing or taking over controls too early, leaves the student to find things out by experimenting on his or her own, later in the career path. A good instructor will use a "teaching moment" to allow the student to experiment under a watchful eye but stop short of exceeding safety limits, keeping the flight always under control.

On the other hand, failing to let students see the consequences of their action, or inaction, is hazardous to the individual's future health. Guarding the controls, helping the student steer well clear of incipient danger, allows the pilot to "graduate" without ever learning anything about the airplane's bad habits. He or she then has to find these things out themselves.

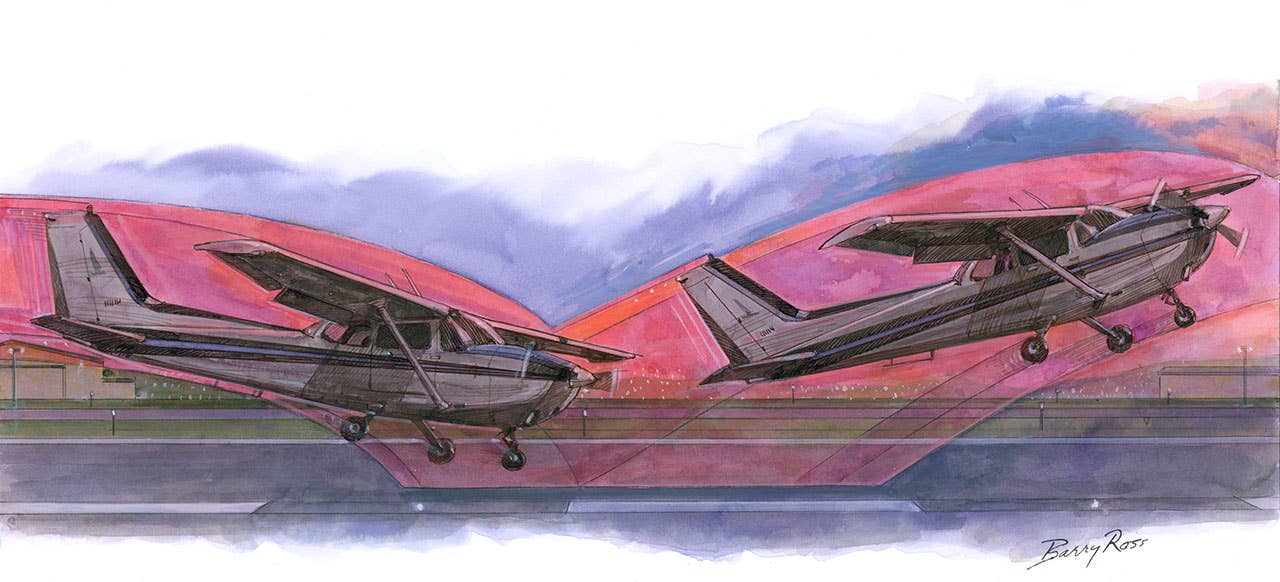

The Cessna 182 is a fine, capable airplane, but it has a heavier wing loading than the 172 that usually precedes it in a transitioning pilot's experience. If its airspeed is allowed to get slow with power at idle during an approach, a high rate of sink will develop that can't be arrested by just yanking back on the yoke during the landing flare. Hard landings from this condition can damage the nosegear, thanks to a 500-pound engine sitting on top of it. Students have to be shown this tendency and learn to avoid it, under a CFI's guidance.

Taking command of a Beech Bonanza is an exhilarating experience for a new pilot, but the airplane's blazing performance and delightful control feel masks a need for strong rudder input during a full-dirty approach stall. Until shown the uncorrected wing drop that takes place, the student thinks they are in full command of a fine aircraft. Without a current-in-type CFI to take them up to an adequate altitude for recovery practice, the checkout isn't complete.

In each of these cases, the instructor needs to know how far to let the situation develop; there needs to be an effective demonstration, so the student can practice avoidance and recovery while avoiding damage to the aircraft or occupants. Test pilots have to know how to expand the envelope gradually, and so should CFIs when training a new pilot.

Transitioning into a new airplane creates an opportunity for heightened risk. In many cases, insurance requirements will mandate a certain number of hours of instruction by a CFI with experience in the specific type of aircraft or some "mentoring" under the tutelage of an experienced, qualified pilot, even though FAA regulations don't require added training. Sometimes these enforced hours produce opportunities to experiment and demonstrate the edges of the flight envelope---which can be a good thing, as long as the participants know what they are doing and don't carry the experimentation too far. However, such training can become too realistic if restraint isn't exercised.

Under the guise of "training," pushing the limits of an aircraft's capability can sometimes go badly wrong. In 2004, two pilots flying a Canadair regional jet on a repositioning flight wanted to see how the aircraft would handle the rarified air at flight level 410, given its light weight. Unfortunately, they didn't realize the narrow "coffin corner" spread between Mach buffet and aerodynamic stall, and the possibility of engine failure; they allowed the aircraft to depart controlled flight, ultimately resulting in a double engine flameout with inability to restart, ending up with insufficient altitude to reach a runway. Both perished, and the aircraft was destroyed, needless losses because no one took charge to minimize the danger of experimenting with the edge of the operating envelope.

Risky Business

Much of our flight training simulates hazardous situations, so students can learn how to recognize the onset of these potential threats and take corrective action to escape their danger. Some of the things we train for are stall and spin encounters, engine failures, hazardous weather management, missed approaches and go-arounds, and rejected takeoffs. Upset recovery training is currently fashionable (and fun), but it's also important to prevent the "upset" from ever happening in the first place.

Breaking the accident chain is one of the instructor's responsibilities, a primary reason for his or her being there. An inexperienced instructor, not quite sure how far to let the student go, may step in too early for effective training, while an instructor with more years of teaching might wait a bit before taking action, for added emphasis. But an older, experienced CFI might also take charge of a deteriorating situation early on, having seen the consequences of going too far and not wanting a repeat. Between these two applications of proper caution, perhaps, are where the instructional failures are likely to occur, resulting in a bent aircraft or worse. Bad things happen when the instructor tries a little too hard to provide "realistic training" without realizing the risk.

Quite often, I have a primary student bring up the subject of spin training; "Do you teach spins?" No, I respond, I teach NOT SPINNING. If a student is fully backgrounded in recovering from stalls encountered from all normally encountered phases of flight, a spin will never occur, because recovery will be made at the onset of loss of control. Lowering pitch attitude to reduce angle of attack always works, so long as the pilot is trained to take action.

On the other hand, approaches to stalls that are terminated with the first stall warning teach very little about the aircraft's behavior if recovery is delayed. At some point, students need to see a complete, breaking stall, manifested by a loss of elevator control or the dropping of a wing. Is this totally safe? No, but neither is having pilots flying around who've never seen what loss-of-control looks like and the panic that can result. The instructor's responsibility is to manage the risk by initiating stalls only at a safe altitude and preventing a prolonged recovery.

I recently had to coach a young man on spin recovery technique as he pursued his CFI certification. He had read the manual and watched the videos, so he thought he knew what to do. The first time he did a spin recovery on his own, he stomped opposite rudder and shoved the stick forward, into about a 1-G negative vertical dive. The airspeed approached redline before I sorted things out for him, and we discussed the need for less-aggressive, by-the-book procedure on the next try.

Dangers Of Overly Realistic Training

In an effort to demonstrate the effect of asymmetric thrust resulting from an engine failure on the takeoff roll, I once allowed a piston-twin student to reach half of Vr speed before I suddenly reduced an engine to idle. As we headed for the runway lights at a 90-degree angle, it dawned on me that this was a very poor procedure. I was simply trying, with too much enthusiasm, to prepare the student for a bad event, and in doing so, I nearly created one. In the future, I briefed the maneuver in advance, made the power cut at a much slower speed, and made sure to do the demonstration on a wide runway.

Another potential trap I encountered was in teaching an instrument takeoff, with the student's view-limiting device in place. While useful as a confidence builder, the ITO really has no place in testing standards or practical flying. It involves aligning the heading indicator precisely with the runway centerline and holding the heading with no deviation until liftoff speed is reached. If the pilot is good, it can be done---but not if a crosswind is thrown into the mix and the student isn't briefed to respond to the instructor's "I have the controls" call. I hadn't considered these two elements, and the student dutifully held his heading while we drifted toward the downwind edge of the pavement. Only a wide runway saved the day.

Twin-engine training has long required a demonstration of Vmc, which calls for placing the airplane into a situation fraught with peril. The student is supposed to learn that, as speed deteriorates, rudder is no longer capable of opposing the asymmetric thrust produced by takeoff power on one engine while the other propeller is windmilling at idle. Carried to extreme, this training can result in the aircraft rolling over on its back and going split-S for the ground. The instructor needs to be fully in the loop, briefing the student carefully on the procedure's risks and making sure he or she reduces power on the operating engine at the first sign of uncontrolled yaw or any other departure from controlled flight. A safe altitude is mandatory. But, although it is tempting to only teach Vmc demos at very high altitudes, doing so reduces the available horsepower that creates Vmc yaw, forcing the aircraft to fly slower in an attempt to demonstrate control loss. A single-engine stall is worse than any Vmc encounter. Again, the instructor must manage the risks.

Training in instrument flight using a partial panel, or no panel at all, is, in part, designed to teach a student the danger involved with loss of power to the gyroscopic flight instruments. Early on, I learned not to allow an inept student to fly too long with the instruments covered. A normal spirally stable airplane will take matters into its own hands within about 45 seconds, as the student tries to use his or her own internal gyros unsuccessfully. A visual recovery is sometimes late in coming, resulting in a G-load build-up at speeds approaching redline. Spatial disorientation demonstrations deliver a valuable lesson but one that you manage carefully.

Teaching instrument flying in actual IMC weather is a worthwhile procedure, but the CFI-I has to realize that his or her workload dramatically increases as attention is diverted between ATC coordination, rescuing a stumbling student and keeping track of the weather situation. "Actual" should be reserved for students who've proven themselves trustworthy at the controls. I've been guilty of trying to finish a training objective in the face of deteriorating conditions, when the flight really should have been called off.

Whenever an accident happens during an instructional flight, we always have to wonder "where was the instructor?," but sometimes it's a matter of trying too hard to do a good job or overconfidence in one's ability to save the day before the crunch comes. Whether receiving training or delivering it, you should never be afraid to voice concern and halt the procedure. If there's any doubt, there IS no doubt.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest Plane & Pilot Magazine stories delivered directly to your inbox