Wings To Fly

A paraplegic’s tenacious journey to the skies

|

My name is Peter Pretorius. My life began in November of 1959 when I entered the world as a healthy seven-pound boy. I started walking at nine months. At the end of 1961, all kids in South Africa were immunized against polio. I developed flu and subsequently wasn't immunized like my two sisters.

Two months later, my mother woke up one morning to find me lying paralyzed in my cot. She rushed me to the hospital, and within a day, I was placed in an iron lung---life support. Polio attacks muscles, but also the nerves between the brains and muscles, resulting in paralysis. My right-hand side was affected quite badly, and my left-hand side recovered somewhat, but the prognosis was that I'd never walk again.

When I was eight, I went in for an operation on my left leg (my strong leg) to remove tissue to transplant to the weak leg. At the time, I had a boil on my knee, which I showed to the doctor before the operation. He was unconcerned. During the operation however, they lacerated the boil, the infection went into the operation wound, and two days later, my toes turned blue. I was rushed to the hospital in Johannesburg with gangrene. After three months in the hospital, my left leg--- my strong leg---had to be amputated.

Childhood was a journey through rudimentary prosthetic limbs and the dream to fly. Despite my physical challenges, or maybe because of them, I loved the idea of flight from an early age; it was the ultimate liberation from the restrictions I had to face. At age 27, I was married and decided that I was in a financial position to start flying. Little did I know how challenging those times would be.

The Directorate of Civil Aviation in South Africa was the authority at the time. They gave my student pilot application one look and said that they were sorry, but I'd never be able to fly---never, ever. The first course of reasoning was interesting: They had found out that one of my eyes had less than 20/20 vision.

|

After two years, when I pointed out that there was a pilot who only had one eye, they finally admitted that the eye wasn't the real problem!the legs were. They were adamant that I'd never be able to use aircraft rudder pedals to the required standard.

It was then that I discovered a Quicksilver Ultralight that had a hand rudder and no ailerons. The Directorate of Civil Aviation had to relent. They were clear, though, that I'd only be permitted to fly an ultralight, and only a Quicksilver at that. But one afternoon, the most beautiful aircraft roared over my head, and I said to my friend, "What was that?"

"An Ercoupe," he said. "It has no rudder pedals."

The sentence was life-changing. Six months later, I was the owner of an Ercoupe. I didn't yet have my PPL, but I needed to convince the DCA that I was imminent pilot material. After purchasing my plane, I thought that I had all the ammo to get my PPL. After many meetings and telephone discussions, I was referred to the Director of Civil Aviation. He peered at me over his desk and concluded that there just was no way in the world I'd be able to get out of an aircraft and 10 meters away in time to save myself if a fire should break out on the ground. I asked him how he'd establish what an acceptable time to evacuate was and what would constitute an unacceptable time. He smirked and replied that he'd use himself as a yardstick against me, as he was a qualified commercial pilot and did internal charter work for the DCA as part of his duties.

|

We met at my aircraft. The stop-watches came out, and the air was tense. I duly offered to go first.

A fireman blew his whistle. I grabbed my crutches, slid the window open and threw them as far as I could. I hooked my elbow into the top window channel, flicked my legs onto the passenger seat with my spare arm, and arched myself backwards, rolling over the doorway.

I landed with a bump on the inner low wing, continuing to roll. I fell flat on my face on the tarmac with a thud. I ignored the pain and breathlessness, spun myself around into a sitting position and sailed away on my behind as fast as I could.

Eighteen seconds, start to finish.

The silence was deafening. The director cleared his throat and climbed into the aircraft. (The Ercoupe is a bit of a tight fit for them plus-sized pilots!) The fireman blew the whistle. The director wiggled for a second or two, lifted his knee and jerked. The little Ercoupe shook and rattled. The honorable director was completely stuck!

Well, I passed my medical and finally got my license. Something, however, kept niggling me. It was the need to show, in no uncertain terms, that I was as able as any able-bodied pilot. I wanted to fly a normal plane with rudder pedals. Two years later, I purchased my first rudder airplane---a Piper Tri-Pacer. To learn to fly it, I had to make a small bracket on the side of the seat that stopped my leg from swinging to the outside when I pushed my foot down onto the pedal, because if I pressed my foot hard onto the pedal, my entire leg would swing outward. I also had straps with clips at the back of my shoe to hook over the rudder pedals, so my feet wouldn't fall off them mid-flight. Since it clipped onto my foot, it wasn't a modification to the plane. Once again, I had to approach the DCA, and the director said, "You can only fly this if you can show you can use your legs." We agreed that he'd come with me for a test flight. So, on the appointed day, we taxied down the runway.

"Line up and take off," he said. He pressed hard on the rudder pedal to the left to see if I could keep it straight, and I corrected. He did the same on the other side. Then he yanked the throttle closed and said, "You're good to go."

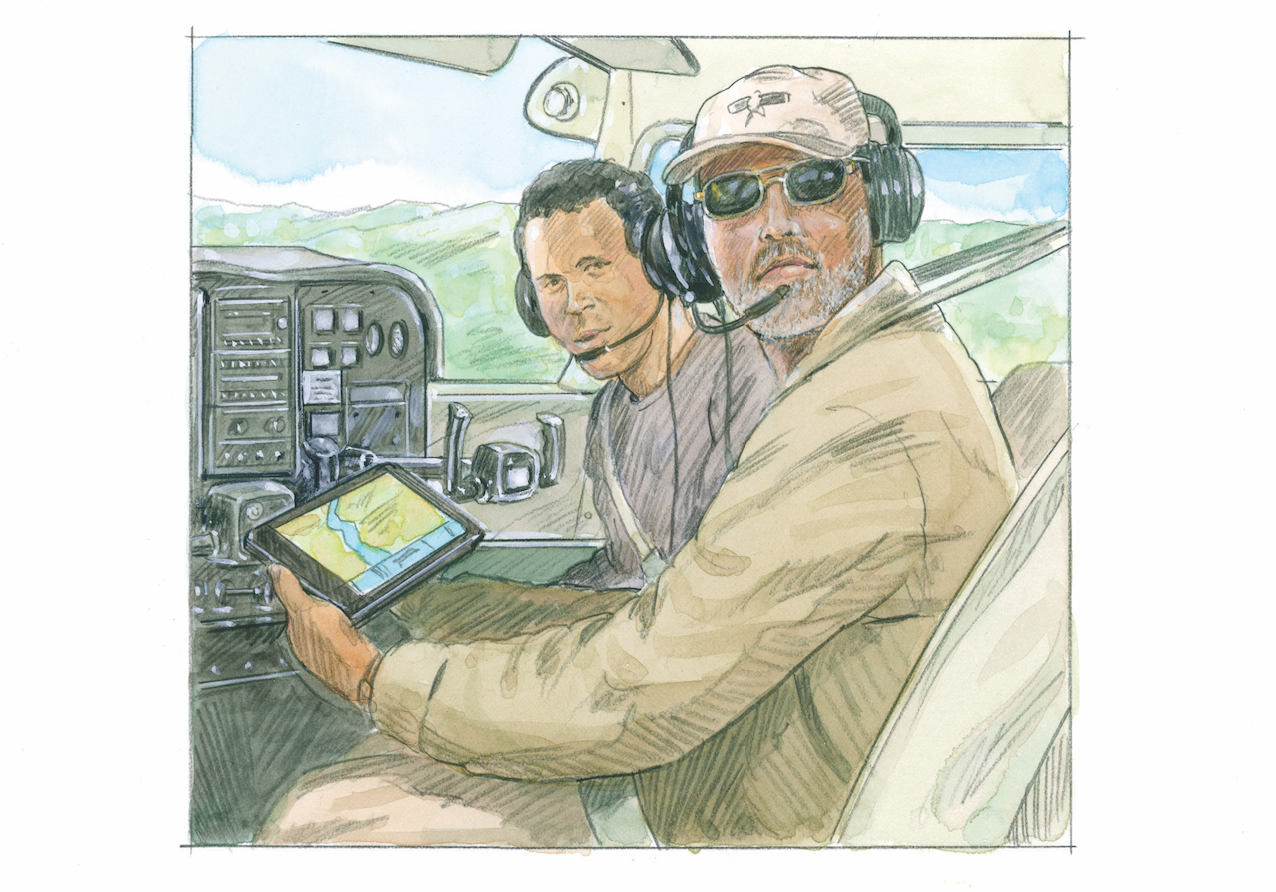

That was the epitome of success. Finally, after five years, I was a pilot who could fly a normal plane. I had also wanted to champion disabled people to enjoy the same activities as those who are able-bodied. Two years later, I received an instructor's rating. Two years after that, in 1992, I became a CFI with my own flying school.

I was one of the first paraplegic flying instructors in the world. To date, I've trained over 400 pilots.

My personal message to you is that you should always know that you can achieve anything in life---if you're prepared to pay the price. Sometimes the price is an emotional one, sometimes it's financial, and sometimes it comes down to sheer determination. But, if you can buckle down and say, "Yep, I'm prepared to do what it takes," then you can absolutely do it.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest Plane & Pilot Magazine stories delivered directly to your inbox