Near-Disaster: Flying A Vintage Piper With Dad

I should have caught the issue on preflight. Truth is, I had never checked this component before, ever.

As the sun peered out above the Atlantic Ocean, the wheels of my Dad's 1951 PA-20 (Piper Pacer) spun free of the runway in St. Augustine, Florida.

Deep breaths of fresh ocean air generated in me a feeling of youthful energy and optimism. This was the first time in a month the Pacer had flown, so we had conducted a thorough preflight under the lights in the hangar before rolling her out onto the predawn ramp to begin our trip. Little did we know, this day would be anything but ordinary as we set out to ferry home the object of my Dad's latest desire.

For years, my then-82-year-old father bought little airplanes, tinkered with them and flew them before finally finding them a new home, and he loved it.

Dad learned to fly at age 15 at Smith Field in Fort Wayne, Indiana. From that day forward, aviation became his vocation, his avocation and his passion. He loved to fly small airplanes, he loved to work on them, and he especially loved talking about working on them.

As the years progressed, the scales had tipped more to the latter, but even at his advanced age, he wasn't all talk.

He was now in pursuit of his newest obsession, a 1948 PA-12, or Piper Cruiser. The Cruiser is the outgrowth of the J-5. It has an odd seating arrangement. The pilot, unlike in the J-3, sits in the front seat, and behind is a pair of cozy seats, side-by-side. It is, in most regards, like the J-5 before it, a glorified Cub, and Dad had his eye on a nice one. He fully expected to conclude the sale and bring home his prize, so I rode along to ferry one of the aircraft back to Florida.

We climbed into the sky with the morning sun and leveled off at 6,500 feet. Small, puffy clouds dotted the royal-blue sky as we began our three-plus-hour trek to western Alabama, where the Cruiser resided.

The outside air temperature was only 51 degrees, but we were quite comfortable due to the heat of the engine and the cozy confines of the small side-by-side cockpit of the Pacer. The Pacer is the four-place, short-wing, tail-wheel predecessor to the more common Tri-Pacer that had its third wheel on the nose. Like many Pacers today, Dad's was actually a Tri-Pacer that had been converted to a tail-wheel.

Engulfed in the subtle smell of old leather, we raced the sun westward at 130 mph, sliding past the small towns of northern Florida and southern Alabama. In time, we approached the airport of our destination town. We followed the given directions from the airport and located the farm where the seller kept the Cruiser.

Circling the property, we spotted an airplane sitting in front of a tin-covered, three-sided barn on the western edge of a large pasture. Having been assured by the owner that the pasture was free of holes, ruts and other surprises, Dad lined up to land on the longest stretch most closely aligned into the wind.

Easing down smoothly onto the soft grass, Dad taxied to the barn and shut down next to what would hopefully soon be his new toy.

After some casual conversation with the seller, my Dad began the two-hour task of inspecting the airplane and its logbooks. Whenever you buy a new plane, you're purchasing a big chunk of the unknown. Are there problems with the new plane? The answer to that is almost certainly "yes." For the flight home, the larger concern in most cases is, is the plane airworthy? Dad found nothing seriously amiss with the Cruiser, he and the seller concluded the negotiations, and we changed the oil in the Cruiser and prepared it for the flight back to Florida.

Our plan was to depart the next morning, so Dad and I chose to fly the Pacer, the plane we flew in with, to the local hard-surface airport for fuel and to secure a room for the night before heading back to the farm field to pick up the Cruiser.

We climbed into Dad's old, faithful ride and, after a cursory preflight---after all, this was not the plane we were concerned about---we cranked up and taxied to the far end of the pasture for takeoff. After completing the brief before takeoff checklist, Dad turned into the wind and added full power.

Are you an aviation enthusiast or pilot? Sign up for our newsletter, full of tips, reviews and more!

As our takeoff roll started, we both noticed the engine wasn't producing full power. Dad first checked the carburetor heat, which was the most likely power thief, but it was off. We were puzzled and continued to check everything we could think of as the Pacer bounced along the ever-decreasing runway.

At what seemed like half power, we slowly accelerated toward the barbed-wire fence at the far end of the pasture. The engine was running smoothly---it just wasn't producing full power, and the obstacle was looming larger and larger.

We were facing a razor-thin margin. Would we obtain flying speed and clear the fence or be just shy of the necessary speed and plow into it? Dad was flying, so it was his call to go or abort. Had I been flying, I might have aborted, but I didn't know the Pacer nearly as well as my Dad. It was his call based on thousands of hours of experience and a couple hundred in the Pacer.

It was clear it was going to be close. After using nearly all available pasture, Dad eased back on the yoke, and the Pacer struggled into the air, clearing the fence by a few feet. I relaxed once we broke ground, but Dad remained focused. He still had trees to negotiate as we continued our stunted climb.

After clawing our way to 1,000 feet AGL, we flew to the local airport and landed without incident. We taxied to the parking area, refueled and tied down for the night. Before leaving for the motel, we inspected the Pacer for anything that might have contributed to the lack of power. Surprisingly, we found nothing. On the way to the motel, Dad called the seller to ask if he could pick us up in the morning so we could keep the Pacer at the airport to take advantage of the longer runway. The seller said, "You read my mind. I was concerned watching you leave here today. Thankfully you made it okay."

He met us for breakfast the next morning, and we drove together to the farm, still thinking about the puzzle, still tied down at the airport. After a thorough preflight inspection and an uneventful takeoff, Dad and I flew back to town. After fueling, we again inspected the Pacer, again trying to identify its problem. Once more, we failed to find a thing. So, since the engine was running smoothly, we decided to fly it home.

I departed first in the Pacer. My takeoff roll was unusually long, and by the time I reached the end of the runway, I was only about 100 feet. Dad took off after I did, and quickly climbed above me.

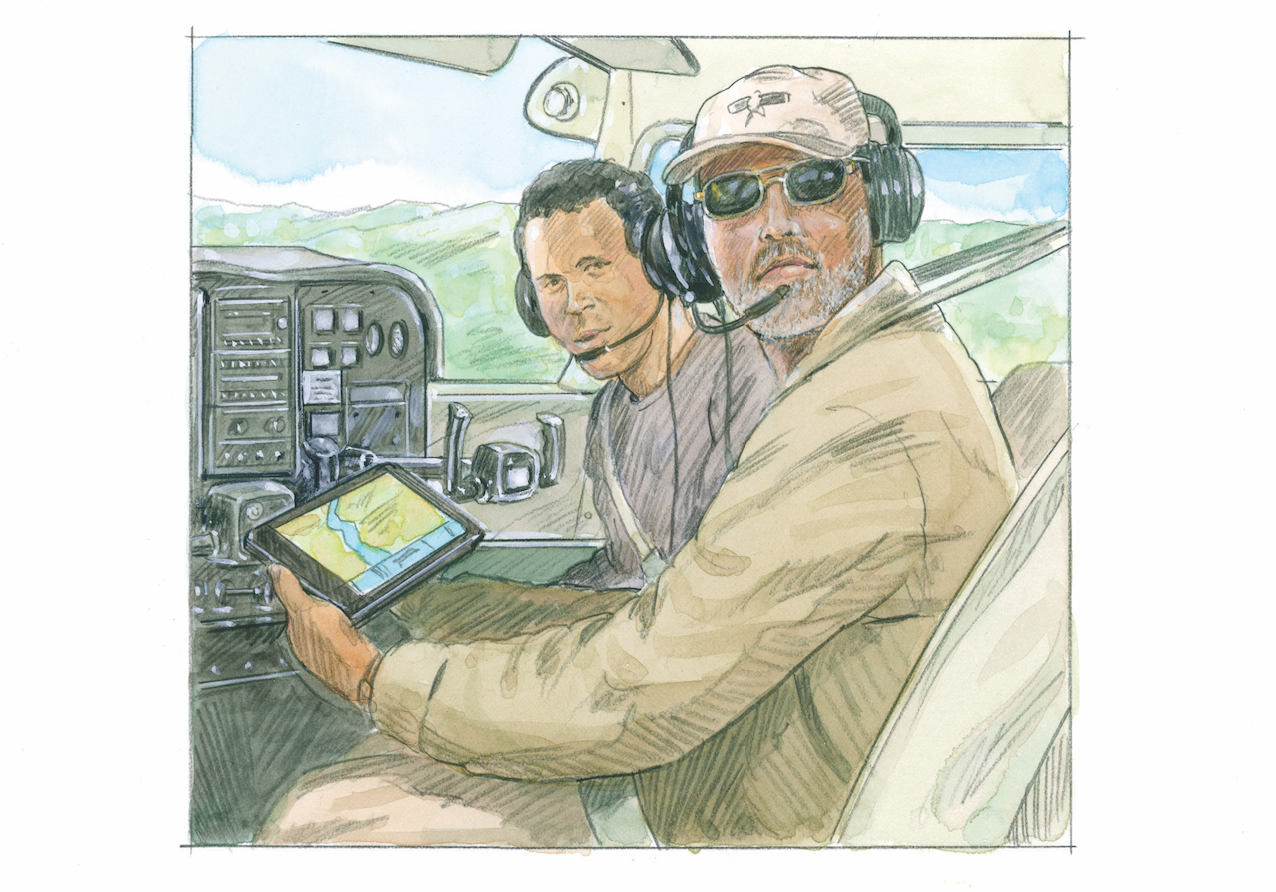

Turning toward home, I slowly climbed to an altitude higher than I would have normally to give myself more options of places to land should the engine quit. Dad and I stayed in close proximity and in radio contact.

After less than an hour, Dad suggested we land in Tuskegee, Alabama, for lunch. I knew that the Pacer's misbehavior was on his mind and that he might have had a good idea, because as soon as we landed and parked, he climbed under the Pacer's engine and looked up into the exhaust stack.

"Aha!" he exclaimed. "The damn baffle has broken off and is blocking the stack."

"What?" I asked.

"Yeah," he said as he climbed out from under the engine. "The baffle has broken loose and is resting on the bottom of the muffler, blocking the stack. That's what is keeping it from generating full power."

Every pilot knows what a muffler is. On the Pacer, it's about 8 inches in diameter and 15 inches long. Welded inside is a smaller cylinder, the baffle, that's perforated all around its circumference. The exhaust gases flow into the baffle and are diffused through the perforations, finally exiting out of the muffler through the exhaust stack.

The weld holding the baffle had broken, allowing it to fall and rest on the bottom of the muffler covering the outlet, where the exhaust gases exit. With the exit blocked, the exhaust gases couldn't flow, creating backpressure, which limited the engine's RPM and, hence, power production.

Greatly relieved at having finally discovered the cause of the problem, we decided to leave the Pacer there in Tuskegee. Dad quickly removed the muffler and placed it in the back of the Cruiser to be taken home for repair.

Do you have an interesting flying story? We are always looking for contributions! Learn how you can write for Plane & Pilot today.

We topped off the fuel tanks of the Cruiser, secured the Pacer, and took off for home.

A few days later, we were back in Alabama with a repaired muffler, which did the trick. A few hours later, we finally got both airplanes home to St. Augustine.

As I think back to this experience, it's a reminder that we're always learning. Sometimes only experience can teach us what we don't know. My Dad's many hours around airplanes helped him think through every minute component that could have contributed to the Pacer's problem. Watching him patiently process what we saw and experienced, both during our preflight inspections and in the air, helped me appreciate that safety in the air is a combination of experience, observation and vigilance.

It's worth mentioning that the baffle came loose on the flight to Alabama but went unnoticed due to the reduced power settings of descent and landing. How often have we skipped the preflight on the second leg because we had just flown the airplane and it was fine?

Will this experience inspire me to do a thorough preflight prior to all flights in the future?

Absolutely. And I'll even look up the muffler.

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest Plane & Pilot Magazine stories delivered directly to your inbox