The Search For Amelia

Sixty-seven years later, the mystery behind the disappearance of Earhart and her Lockheed Electra might soon come to an end

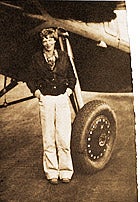

Lady Lindy always knew how to captivate a crowd. And today was no different. She, famed aviatrix Amelia Earhart---nicknamed for her comparable achievements to another celebrated aviator, Charles Lindbergh---stood in front of her airplane amidst a throng of people who were eager to witness her attempt at yet another record-breaking flight---to become the first person to fly around the world at its widest route, near the equator. Earhart and expert celestial aerial navigator Fred Noonan will take what she calls her "flying laboratory," a twin-engine Lockheed Electra L-10, and attempt to cross 29,000 miles of land and sea.

Lady Lindy always knew how to captivate a crowd. And today was no different. She, famed aviatrix Amelia Earhart---nicknamed for her comparable achievements to another celebrated aviator, Charles Lindbergh---stood in front of her airplane amidst a throng of people who were eager to witness her attempt at yet another record-breaking flight---to become the first person to fly around the world at its widest route, near the equator. Earhart and expert celestial aerial navigator Fred Noonan will take what she calls her "flying laboratory," a twin-engine Lockheed Electra L-10, and attempt to cross 29,000 miles of land and sea.

The journey would prove to be a monumental challenge. And nobody at that moment, it seems, knew this better than Earhart herself.

"I have a feeling that there is just about one more good flight left in my system," confides Earhart to the crowd before stepping on board the Electra. "And I hope this trip is it."

There was no way that anybody at the time could have realized just how eerie those words would become. On July 2, 1937, a month after Earhart uttered that statement, she and Noonan departed from Lae, Papua New Guinea, and headed for Howland Island, a mere speck in the mid-Pacific that measured one-and-a-half miles long and a half-mile wide. The U.S. Coast Guard cutter Itasca was stationed off its waters to act as the Electra's radio contact. In the hours that followed, Earhart sent eight transmissions to the Itasca, most of which indicated she was lost and having radio problems. At 8:22 a.m., Earhart contacted the Itasca for the last time. What happened next is---quite literally---anybody's guess.

Running On Empty

David Jourdan is no stranger to finding lost treasures. His deep-ocean exploration search firm, Nauticos, which boasts a Titanic discovery team member on its roster, has a long list of credits to its name, including the underwater discoveries of the I-52 Japanese submarine, the Japanese aircraft carrier Kaga and the Israeli submarine Dakar.

So it was only natural that Jourdan meet his match---the missing Electra. The opportunity presented itself when he met Elgen Long, a longtime pilot and author of Amelia Earhart: Mystery Solved. Long subscribes to the theory that the Electra simply ran out of fuel and crashed in the ocean. He took an accident investigator's approach to the Earhart disappearance and collected reams of materials that included interviews with the people who listened to her final transmissions to the Itasca. He theorized that radio propagation analyses, combined with navigational and fuel consumption analyses, will reveal the Electra's final resting place---in the middle of the Pacific Ocean.

"If you look at the map of the South Pacific," clarifies Jourdan, "the amount of land, compared to the amount of water, is a small percentage. She'd be much more likely to end up in the water than on land if she was lost."

It was so compelling that Jourdan enlisted the help of Rockwell Collins' expert radio ham operators Tom Vinson and Rod Blocksome to aid with the radio signal propagation analysis of Earhart's final transmissions to the Itasca. Through computer models, flight simulations and Nauticos' own navigational analysis, Vinson and Blocksome meticulously pieced together the strength of each radio signal recorded on the Itasca's logbook to estimate how far away the Electra was at each of the transmissions.

The results of the analyses finally culminated in March 2002, when Nauticos led an expedition to search 1,000 square nm of the ocean bottom in the waters off Howland Island. Using a sonar search system called NOMAD, the team scanned the bottom of the ocean floor for anything that would indicate an airplane wreckage of some sort. After having covered 630 square nm, however, a hydraulic leak, failed winch and damaged hydraulic pump sent the crew sailing back home---empty-handed.

But this unexpected event hasn't stopped Jourdan from going back. "We had uncovered 630 square nm of ocean bottom," asserts Jourdan with pride. "And on our next trip, we won't have to look there again. We know it's not there. So we need to finish what we started, and I think the chances are as good as ever that Earhart's plane would be found in that remaining area."

|

| For six weeks, the ship called the R/V Davidson was home to the Nauticos team while they searched 630 square nm of the ocean floor for the Electra. |

Paradise Lost

But Richard Gillespie, executive director of the nonprofit organization The International Group for Historic Aircraft Recovery (TIGHAR), disagrees. He, unlike Jourdan, believes that Earhart crash-landed on Nikumaroro Island, an atoll in the Phoenix Islands in the South Pacific, and died of thirst.

"The trouble is that there's no indication that she crashed at sea," explains Gillespie. "There was no distress call. There was never any floating wreckage found, not even an oil slick."

TIGHAR started its search around 15 years ago, when TIGHAR members Tom Willi and Tom Gannon asked Gillespie to consider their theory about the Earhart disappearance. They explained how celestial aerial navigation works and the significance of Earhart's last transmission to the Itasca, when she said, "We are on the line 157-337." They claimed that if she was running north and south on that bearing with three hours of fuel left in her tanks, she would end up at Nikumaroro Island. But what prompted Gillespie to fully commit to the project was the fact that the uninhabited island was never ground-searched by the U.S. Navy, even though there were signs pointing to human life at the time, including an airplane wreckage, stories of two stranded fliers and even a Caucasian female's bones.

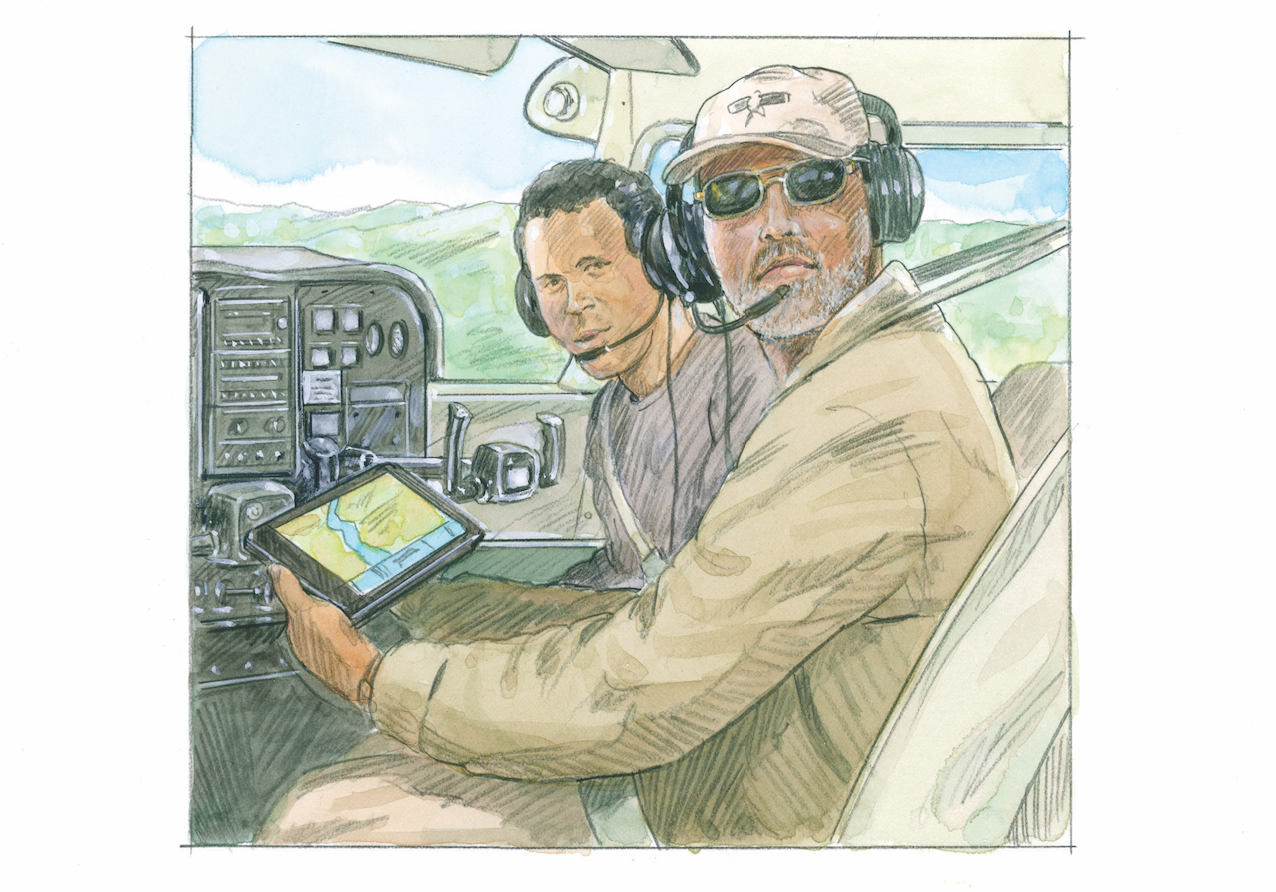

So, armed with a team of experts consisting of archaeologists, forensics scientists and aircraft-recovery specialists, Gillespie launched eight excavations to Nikumaroro Island, where he melded two seemingly different treasure-hunting techniques---19th-century archaeology and modern-day forensics. "We use things like GPS for locking positions, metal detectors for airplane parts and some modern types of surveying equipment for the archaeological work. But generally speaking, it's traditional forensic archaeological science," describes Gillespie.

And the result of the merger was nothing less than astounding. Gillespie has amassed hundreds of artifacts, which he believes could eventually solve the 67-year-old mystery. Although most of them have yet to be identified, Gillespie remains optimistic that he'll find something soon, if not among the artifacts that he's already collected, then on his next trip, called the Niku V, scheduled for Summer 2005.

"There's a tremendous amount of evidence there," says Gillespie with excitement in his voice. "But extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence. We're getting there."

Mythical Proportions

In addition to Nauticos and TIGHAR, several others are hot on the trail of the Electra. One recent report claimed that John Naftel, an 81-year-old war veteran asserting to have participated in the burial of Earhart and Noonan on the island of Tinian in 1944, will help in finding their grave site. A different report suggests that there is evidence that Earhart was captured by the Japanese, secretly repatriated and lived out her life in New Jersey under the pseudonym Irene Craigmile Bolam. And yet others believe that she was the voice of radio broadcaster "Tokyo Rose" in WWII... And the list goes on.

With so much conjecture about the final hours of one of aviation's most beloved female aviators, one of them, one would think, is bound to hold the truth. But whether or not anyone will be able to find it anytime soon still remains to be seen.

In the meantime, as the search for Earhart and her Electra---the holy grail of aviation---rages on, some have taken comfort in a letter Earhart wrote to her husband, George Putnam, in the event that a dangerous flight would prove to be her last: "Please know I am quite aware of the hazards. I want to do it because I want to do it. Women must try to do things as men have tried. When they fail, their failure must be but a challenge to others."

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest Plane & Pilot Magazine stories delivered directly to your inbox