Upgrade Your Plane! Part III

Firewall forward’life after TBO

In previous issues, we took you through upgrading an aircraft exterior (P&P Dec. 2009) and an aircraft panel (P&P Jan./Feb. 2010). Now, we go firewall forward.

In previous issues, we took you through upgrading an aircraft exterior (P&P Dec. 2009) and an aircraft panel (P&P Jan./Feb. 2010). Now, we go firewall forward.

When purchasing an aircraft, the selection criteria usually relate to mission capabilities such as seating capacity, speed, range, weather capabilities, etc. Consequently, the first engine-related decision that most aircraft owners make comes at TBO (time between overhauls). Granted, there may be some decisions about engine replacement parts along the way, but by and large, what to do upon reaching TBO is a decision that always looms large just over the horizon.

For many owners, the TBO process isn't fully understood. For me, researching my options made the decision at TBO clear. The nuances of the decision process are worth pondering. There are five basic options to consider upon reaching TBO. We'll discuss each in detail so you can fully understand and appreciate the significant---and oft misunderstood---differences. To begin, we must first understand what the term "TBO" means.

Every engine is assigned a TBO value from the company that designed, certified and manufactured it. For piston engines, these values can range from 1,200 to 2,400 hours, with 2,000 being the most common. There also is a 12-calendar-year TBO for engines, which is largely ignored. Regardless of whether it's based on calendar years or running time, the TBO value really is nothing more than a recommended service interval assigned by the manufacturer. The TBO is neither a manufacturer guarantee that the engine will last that long nor an FAA-required maintenance interval (unlike an FAA-mandated annual inspection). TBO simply is an original equipment manufacturer (OEM) recommended service interval with a margin of safety built in.

|

The Options

Each of the five options has its unique attributes; but you may be surprised to learn that the nuances between them are more than semantics. So here they are, roughly in order based on price (from most to least expensive).

⢠Factory New: If you've been squirreling away money in an engine reserve for the last 2,000 hours since your aircraft (or engine) was new, you may opt to purchase a brand-spanking-factory-new engine. The factory-new engine is a new zero-time engine that reflects all of the latest production improvements; it's compliant with the latest service bulletins and airworthiness directives, and has the longest factory-backed warranty available. It's also the most expensive of the five options. But if you want an engine that's 100% new---just like the day the aircraft was first delivered---then this option is for you. All of the remaining options make some sort of concession to lessen purchase price.

⢠Factory Rebuilt: Sometimes the terms "rebuilt" and "overhauled" get used interchangeably. Adding to the confusion are statements like "rebuilding the engine to zero-time limits" or "to new tolerances," etc. One key difference between a

factory-rebuilt engine and an overhauled one is that only the engine's OEM is FAA-authorized to rebuild (i.e., "remanufacture") engines. Only the OEM can claim that factory-rebuilt engines are zero-time powerplants just like factory-new engines. This primarily is because the factory-rebuilt engine is built anew on the same production and assembly line as factory-new engines, which ensures that rebuilt engines are assembled to the same tolerances and limits as new engines, in accordance with the same quality management and under the same FAA production certificate scrutiny. For these reasons, factory-new and factory-rebuilt engine benefits are virtually indistinguishable. The chief differentiating factor between a factory-new and factory-rebuilt engine is that the rebuilt engine may contain cores (i.e., crankcases, crankshafts, etc.) that have been refurbished to new specifications. The limited use of cores in factory-rebuilt engines is what accounts for the slightly lower price than factory-new engines with brand-new parts.

⢠Factory Overhaul: Some engine manufacturers (such as Lycoming) also overhaul engines. This has benefits for both consumer and manufacturer. For the manufacturer, it means engine data plates won't be overhauled by third parties who might not know what they're doing. For the consumer, it provides an even more price-competitive alternative over a zero-time rebuilt engine.

The chief differentiating factor between a factory-rebuilt and a factory-overhauled engine is engine time---and this is a significant key difference. No company, not even the OEM, can overhaul an engine to "zero time" like a factory-new or factory-rebuilt engine. For those inclined to go the overhaul route, there are two major benefits of a factory overhaul compared to a field overhaul: parts and tolerances.

Because the OEM is overhauling the engine, you can rest assured that only genuine OEM parts are used. Additionally, since the OEM built the engine new, only the OEM truly knows the engine's manufacturing specs. Granted, most field overhaulers claim to overhaul engines to "factory-new specs," but the OEM only publishes data based on service limits, not manufacturing tolerances. Thus, it stands to reason that the factory-overhauled engine will conform to a tighter set of tolerances than a field overhaul.

⢠Field Overhaul: These are performed by third-party engine shops. As you can imagine, there's a wide range of expertise between shade-tree overhaulers and world-class maintenance, repair and overhaul (MRO) shops, so quality control is something you'll need to gauge for yourself. Some field overhaulers have built strong reputations for delivering a quality product at a fair price. And while it's not our intention to convince anyone that one of the above options is better than another, there are key points of differentiation.

The 1971 Piper Cherokee PA28 received a paint, panel and engine upgrade. |

The field overhaul is unique among the aforementioned options because it doesn't use 100% original equipment parts. Field overhauls are done by independent businesses, and they're free to substitute parts that aren't original equipment. While not OEM parts, aftermarket parts must be manufactured by a company authorized by the FAA with Parts Manufacturer Approval (PMA) to ensure each part is certified for installation on engines as a direct substitute for the OEM part. The use of PMA parts may help the field overhauler further reduce price, provided that the PMA parts are less expensive than the OEM parts. Generally, the consumer has no way of knowing which engine parts are OEM versus PMA unless the overhauler produces a complete parts list from the overhaul.

Consequently, there may be less than 100% OEM parts in a field-overhauled engine, which is okay, because the PMA parts are FAA-certified. Additionally, the field overhauler may use or reuse more cores than the factory overhaul if the subject parts are deemed to be "serviceable" or within the specified service limits. But remember, the engine manufacturer only publishes service-limit data/specs, not proprietary manufacturing specs, so the tolerances on a field overhaul may not exactly match the OEM spec on a manufactured or rebuilt engine.

Furthermore, just as with a factory overhaul, by definition, the field overhaul isn't a zero-time engine. Thus, if the engine had 2,132 hours on it before the overhaul, it still has 2,132 hours on it after the overhaul. Although the engine may be rightfully positioned as a "zero-time-since-overhaul" engine, it's still a 2,132 total time engine. This means that no matter how shiny and new the overhauled engine appears after the overhaul service is performed, the entire engine history follows the engine. Even if the engine was completely overhauled after a prop strike, the history on that engine's data plate will reflect the prop strike.

⢠Do Nothing: Finally, one option is to simply turn a blind eye and do nothing. Since TBO isn't a milestone for engine repair or replacement, the operator may opt to run the engine beyond TBO. While operating an engine beyond the manufacturer's suggested limit is a personal decision, there are steps you can take to increase your odds of continued safe operation until such time when the engine itself decides that it's time for an upgrade.

Since the FAA-mandated annual inspection includes a cursory engine inspection, early signs of engine wear may be detected through the basic compression test. In between the annual inspections, the prudent way to monitor engine health is through oil analysis. By continually monitoring the engine oil (with increased frequency as the engine clock ticks up), the amount and type of contaminants in the oil will indicate which engine parts are wearing and at what rate (normal wear versus trends that may indicate a component-specific failure is imminent). In fact, it may be beneficial to periodically submit an oil sample between oil changes if you push beyond TBO. In the grand scheme of things, oil analysis is inexpensive and can provide advanced warning about the health of your engine that you can't possibly know until the fan stops turning.

Value Proposition

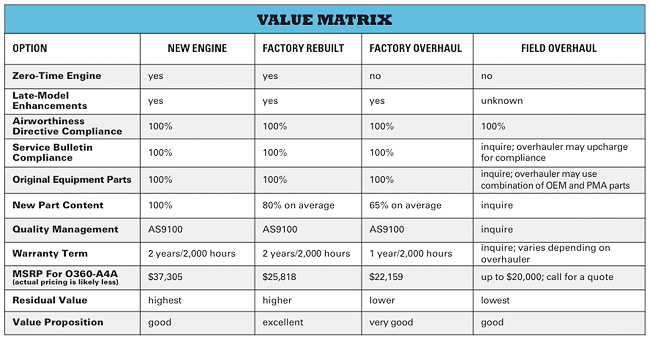

Clearly each aircraft owner must individually determine the most important elements of the upgrade---price, warranty term, warranty coverage, engine time, new part content, residual value, etc.---to determine which represents the best value. In my case, it became obvious after plotting the options in a matrix (page 57) that purchasing a factory-rebuilt engine was the clear winner. Purchasing a fully airworthiness directive-- and service bulletin--compliant zero-time engine built on the same line as factory-new engines, under the scrutiny of an AS9100 Quality System and FAA production certificate, and using 100% OEM parts---all for less money than a brand-new engine---seemed like the greatest value. Plus, I was the beneficiary of some production improvements, like roller tappets that a field overhaul may not have included. Any way you spin it, upgrading an engine is a decision that you'll be living with for a long time (almost as long as it will take for the bite in your wallet to heal). So the better you understand the differences between your options, the better informed your firewall-forward upgrade decision will be and the more satisfied you'll be as an aircraft owner.

| A Fresh Start Four tips for an upgraded engine |

| No matter which upgrade option you select at TBO, there are some "best practices" you should implement when starting fresh that will help protect your investment and ensure that you get the maximum service out of your upgraded powerplant. Engines that are abused or neglected likely will never reach TBO. Conversely, engines that are operated frequently in accordance with OEM operation guidelines and best practices can surpass TBO. The best way to monitor the health of an engine over time is to conduct an oil analysis at every oil change and monitor the trends in oil contamination. Here are four best practices you should consider adopting.

1 HAVE A PLAN: Every time you change your engine oil, send a sample off for analysis. Establishing a baseline and monitoring trends in engine wear provides an early warning system that will save you far more than the cost of the analysis itself. To get the most comprehensive oil analysis available, select one company and stick with it. Analyses performed by different laboratories may result in inconsistent results. To really establish a baseline that can positively identify trends versus variations in analyses, select a single company and use it every time. While there are a number of companies that perform aviation oil analysis, Aviation Laboratories (www.avlab.com) is the only company solely dedicated to aviation. Any company with a specialized focus likely does its job better than the rest. 2 USE THE BEST OIL FILTER: In aviation more than anywhere else, saving a few bucks doesn't always pay off in the long run. Although I've been known to fly out of my way a bit to save a few bucks on fuel, I never purchase oil filters based on price. Using a premium filter is a small investment in engine longevity. Filters vary by manufacturer, but there's one that clearly rises to the top in terms of filtering ability and features---Tempest (www.tempestplus.com). The oil analysis process only allows for the detection of wear particles that are between one and 12 microns in size. Most oil filters trap wear particles that are 30 microns and larger. Therefore, typical oil analysis combined with filter debris analysis aren't measuring contaminants between 12 and 30 microns. The Tempest oil filter has a unique magnetic disk that traps ferrous contaminants smaller than 30 microns, preventing such particles from continuing to circulate in the engine lubricant. Analyzing these trapped particles can help identify signs of progressive valve stem or cam wear before more costly repairs are needed or a catastrophic failure occurs. 3 MONITOR ENGINE PARAMETERS: If your aircraft isn't already equipped with an engine analyzer, this is a perfect addition to your engine upgrade. There are scores of digital and analog systems available, but one thing is for certain, managing and monitoring critical engine temperatures (i.e., cylinder heat temperatures, exhaust gas temperatures and/or turbine inlet temperatures) takes the guess work out of engine tuning at altitude, and provides an added level of peace of mind and economy. 4 INSTALL AN ENGINE HEATER: Few things shave hours off your engine's life as much as cold starts. Repeatedly cranking a cold-soaked engine when the tolerances are at their tightest and lubrication at its weakest will surely lead to early retirement. For anyone living in a cold climate, installing an engine heater will help your engine last longer and help you do more flying in the winter months. There are a variety of engine preheat systems that keep oil and/or cylinders warm. One of the best is by Reiff (www.reiffpreheat.com); it's perhaps the most versatile, least intrusive and---wait for it---least expensive. The Reiff system doesn't require the replacement or substitution of any factory-installed engine parts and won't interfere with engine monitoring systems. Naturally, this plays well with the concept of adding an engine analyzer. |

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Get the latest Plane & Pilot Magazine stories delivered directly to your inbox